Originally posted in December, 2009.

Folks,

16 December 1944 saw the opening of the German offensive later known as the Battle of the Bulge. Remember, as you mark this day, Eric Fisher Wood, an American warrior, a man who more than any other single man, made a material difference to the outcome of the battle. His story is inspiring, almost electrifying, in its incredible details. The fact that his name is almost entirely unknown to this generation of Americans condemns us all.

One of my favorite subjects of study is the American army in defeat -- Philippines, 1942, Kasserine Pass, 1942, Battle of the Bulge, 1944-45, Korea, June, 1950 & November, 1950 -- for only in defeat do you see the best and the worst of humanity and in that terrible crucible learn lessons that are visible nowhere else.

Rifleman Dodd by C.S. Forester is likewise one of my favorite novels. Dodd, skirmisher of the 95th Rifles in Wellington's Army during the Peninsular War, was cut off from his unit as it retreated. His story of continued resistance against all odds was written in 1932, first published in England under the title "Death to the French." By the time Eric Fisher Wood entered West Point it was popular reading among cadets. One can only speculate what effect Rifleman Dodd had on the young plebe. What is certain is that Eric Fisher Wood, an American Dodd, outdid his fictional hero by a country mile. I will have some more comments on the other side of his story.

Mike

III

The Lonely War of Lt. Eric Fisher Wood, Jr.Saturday Evening Post, December 20, 1947 by R. Ernest Dupuy, Col. USA, Ret.

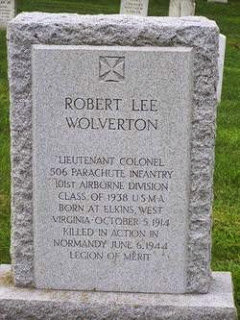

Told for the first time, the story of a young lieutenant who almost single-handedly saved the right flank of an American army in the Battle of the Bulge, "the most amazing example of heroism in World War II."

DARING indeed would be he who named one individual as the epitome of human heroism. Through the ages, men of all nations and all races have fought well and died well. Once in a great while, however, a man emerges who, under extraordinary circumstances, flings down the gauntlet to death, defies fate, says farewell to the conflict only when breath leaves his body. Since chance - and chance alone - decides whether or not there be witnesses to such an exploit, let us say of what follows only that it is the most amazing example of heroism as yet to come out of World War II.

The man was a first lieutenant, Field Artillery, AUS, one of thousands bearing identical labels. The cannons were squatty, humped-up, wicked looking pieces towed by great six-by-six trucks- three of thousands of the same type carried on Ordnance records aa "Howitzer, 105 mm., M1." There the resemblance of this man and these cannons to others of their respective kinds ceases. For the cannons saved the right flank of an American army in the Ardennes. And had it not been for the man, they wouldn't have been available to do it. After the cannons bad been lost with honor when howling waves of the Nazi 2nd SS Panzer Division washed over both them and the remnants of the field artillery battalion serving them, the man continued to wage single handed warfare against the 6th SS Panzer Army. So the man, as always, is the important element. And his tale is worth the telling.

It begins on December 16,1944, when the Battle of the Bulge broke furiously on the Ardennes front. The howitzers - there were four of them to start with - of Battery A, 589th Field Artillery Battalion, 106th Infantry Division, emplaced in rear of the little village of Schlausenbach on the north- western slopes of the Schnee Eifel, were, with the rest of the battalion, supporting the 422nd Infantry Regiment of the same division. 1st Lt. Eric F. Wood, Jr., from Bedford, Pennsylvania, twenty-five year- old Princeton fullback, five feet eleven, 195 pounds in weight and catlike in reflexes, was executive officer of the battery. His skipper, Capt. Aloysiua J. Menke, up at a forward OP, was silent. He would continue to be silent, for the first kraut wave had overrun the OP, and Menke, a prisoner, will not enter this story again. Wood was then acting battery commander.

Up the forest through a gaping hole torn in the northern sector of the 106th Division's recently inherited cordon defense positions, the Germans were swarming around the left flank and rear of the infantry, and into the artillery positions. Three German tanks pushed along the road, one leading on the road and two others off the road in the draw behind the leader. Lt. Wood, from his command position, shouted commands to his No. 1 piece gunner, John Gatens, who with two shots destroyed the lead tank by direct fire. No. 1, incidentally, was the only piece in the entire battalion which could reach any of the defilade tanks. Lt. Wood, the previous day, had arranged for No. 1 gun to be placed so that it could sweep the road. The lead tank destroyed by No. 1 gun, Wood then ordered all four guns to fire on the remaining tanks that were below the hill. He did this with high elevation fire, using one powder bag instead of seven. The remaining two tanks were disabled by this "indirect fire." He then swept the woods around him with short-cut fuse, breaking up the enemy's infantry support.

All this was but a temporary respite.. By nightfall the battalion was ordered to fall back; the krauts were crowding in from all sides. But getting out was easier said than done. In the Battery A positions the big tow trucks churned the icy muck to a paste in which the howitzers sank almost hub deep. Hostile fire, small arms and artillery was sweeping the area. Snow blew patchily into sweating faces in the night. The wind howled through trees each of which might be hiding an infiltrating enemy soldier. Hostile flares flickered over the snow drooped pines. It was not nice. But Eric Wood tore around, and the men of Battery A tore and tugged with him. He was that kind of guy. At last they got the howitzers on the road one by one, with two trucks grinding at each piece and with little clumps of men pushing, like ants tussling with twigs. The howitzers could shoot again, once they dropped trails, for Eric Wood had packed eighty-three rounds of ammunition for each piece in the trucks. In the rest of the battalion Battery C never got out. The pieces, too deeply mired, had to be blown up. That left eight howitzers out of twelve. Battery B got out ahead of A, and the outfit went swaying and fumbling in the dark over a narrow corduroy trail, while the enemy, with white phosphorus shells, hunted for them.

They got to their new positions by dawn. A field on the right of the road that runs north from Bleialf into Schonberg on the Our. They were about a mile and a quarter from Schonberg itself. Battery B got in first. Wood got three of his howitzers in. The last one, lagging, its tow truck partly crippled, he held on the road as antitank defense. The Germans were really bursting through in force that second morning. From the north they were coming down the Our valley into Schönberg; from the south they were coming up this road from Bleialf. But all that Eric Wood knew was that the world seemed full of krauts. The enemy from the south washed nearer, overrunning their neighbors. The acting battalion commander - the original was cut off behind them with Battery C - ordered the outfit out, to push through Schönberg and west toward St. Vith. Wood got two pieces rolling and sent the crippled third howitzer back with them. "I'll meet you west of Schönberg," he told the section chief, Sgt. Barney M. Alford, "if I get there."

For Wood's last howitzer was stuck. Once again the perversity of inanima to objects was working against him. So he stayed to get it out, with its crew. They worked at it while more krauts began to overrun Battery B, and its howitzers were abandoned. That, of course, left four howitzers in the battalion, out of twelve. When Wood at long last got his last piece on the road and swung over the tail gate of the truck, the last man out, the main body of the 589th Field Artillery Battalion consisting now of Wood's three other howitzers and some truckloads of men of both batteries, was way ahead of him. This bedraggled outfit hit Schönberg to find the krauts coming in from the north. The three piece "battalion" beat them to the Our River bridge by seconds, and got away. It got away to fight again, beginning on December nineteenth, at a dreary crossroads far to the west on the hastily forming and still somewhat nebulous right flank of the United States 1st Army. How these three howitzers for four days saved the right flank of the 82nd Airborne Division and of the Army at "Parker's Crossroads" is another story.

When Eric Wood and the twelve men with him in the truck now came rolling down the steep hill into Schönberg the howitzer bounding behind, a kraut tank poked its nose out of the southern entrance of the village. Brake bands screamed as the truck pulled up in front of it. Wood and his men piled out to attack it. Pfc. Campagna had a bazooka, the others their carbines. But the tank wasn't having any - God knows why! It scuttled crab like back across the bridge and disappeared into the town with Wood and his gang in pursuit. They crossed the bridge and pointed west in Schönberg's one street, with snipers pecking at them. And they slowed down while Sergeant Scannapico and Pfc. Campagna, still hugging his bazooka, ran ahead to see where that tank had holed up. They found it tucked in an alley. Scannapico fired his carbine at it. Campagna, climbing into the truck, let fly with his bazooka as they rolled past. Again the tank wasn't having any. The truck slowed to let Scannapico catch up, but a sniper got him cold. So the section rolled on. They gathered speed as they left the village and met, over a rise in the road, another kraut tank. A medium, this, with its cannon and machine guns trained directly on them.

Wood's reflexes worked instantaneously. He pitched his men and himself out into the ditch an instant before the tank's artillery blasted the truck to scrap iron. That was that, so far as getting the howitzer back safely was concerned. It left the battalion's score at three out of twelve. But what about Wood and his men? The enemy was firing at them now from across the river on the right. Kraut infantry were firing from the trees beyond the meadow across the road to the right rear. More kraut infantry was pouring out of Schönberg behind them. And that tank squatted in front of them a stone's throw away. To the ordinary man, the situation seemed hopeless. And all but one of the group were ordinary men. They raised their hands to surrender. They were through. But Eric Wood wasn't through. Leaping the ditch, he ran, dodging northwards the trees. The others could see kraut bullets sending little squirts of snow puffing up in the meadow at his heels, until he disappeared from sight in the shelter of the forest.

Late in the afternoon of the next day, December eighteenth, Peter Maraite, woodsman, left his home in the mountain village of Meyerode, Belgium, about four miles north of where that tank had smashed Eric Wood's truck. There were Germans all around. There had been fighting; doubtless there would be more. But Maraite had something else to think about. He was going to Cut a Christmas tree - there had always been a tree in the Maraite house for Christmas; there always would, as long as Peter could provide one. They are like that, in the Ardennes, war washed for generations. So Peter plodded for a mile through the woods, moving southeast in the general direction of Schönberg. It was cold; clammy mist cloaked the woods. The snow powdered his head as he brushed low branches. Then two armed men loomed in front of him at a six way trail crossing - Americans. Peter knew Americans when he saw them; they had held this sector for more than two months now. One was a big man with single silver bars on the shoulders of his short overcoat. He had a pistol. The other was smaller and wore no insignia of rank. He was armed with an infantryman's rifle, not an artillery man's carbine.

Peter Maraite is insistent on this point. Now, like most of the Belgians of this border country, Peter Maraite spoke only German. The Americans could not speak German. But Peter managed to convey the idea that he was a friend; he invited them home. Cold, wet and tired, they accepted. Because of the Germans, they came home cautiously, slipped into the warm stone house where astonished Anna Maria, Peter Maraite's wife, and wide eyed Eva, their daughter, rushed to pour hot coffee. The Americans gulped it down while Eva slipped out to bring back Peter's trusted friend, and neighbor, Jean Schroder, who spoke English. The watchdog was put outside to guard the door. The Americans relaxed, steaming their soggy clothes before the fire. The big young officer, with a confident, smiling face, told how he had escaped from a detachment surrounded near Schönberg. He and his companion were going to St. Vith. He was concerned about the fate of his men, "all very good and loyal men," as Peter Maraite remembers the conversation. The villagers warned that the country between Meyerode and St. Vith was full of Germans.

The young officer wasn't a bit disturbed by their shaking heads. "I'll either fight my way back to my outfit," he told them, "or I'll collect American stragglers. I've seen some in the woods around here and I'll start a small war of my own." What he wanted now was information about the Germans. He pulled out a map. So, while the woman and the girl bustled to get supper, the young American officer and the two droopy- mustached woodsmen pored over the map. The Americans couldn't go that night, the villagers said; they would. So the two Americans ate and drank with their hosts. The officer cracked jokes "said funny things which made us laugh," is the way Peter and Anna Maria Maraite put it. He seemed to have no fears. After they cleaned their weapons, the Americans repaired to the big soft feather bed while their clothes dried. They slept the sleep of tired but confident men, not waking even when a V bomb crashed in the outskirts of Meyerode with its hideous thunder.

The Maraites at first wondered if their American visitors had been among those captured on the Ades Berg. Perhaps - but odd things were happening in those woods southeast and east of the village, deep behind the German lines in the dense Omerscheid area of the Bullingen Forest. Daily, bursts of small arms fire came from the hills, and sometimes the "wham" of a mortar. These sounds were in addition to the crashes of bombs and pom-pomming of flak guns along the highways to the west. The weather had cleared and the Allied air forces were taking toll of German columns. Fighter bombers continually strafed the roads. The Germans had had to reroute their daylight movements through the secondary roads in the eastern woods leading to the Our Valley and thence through the Losheim Gap. It was from this area that those unexplained small arms bursts were coming over the cold air to the peasants huddled in their homes. Meyerode people began to notice that while large forces came and went at will through the hills, never did a small body of Germans or a supply column pass into the pine woods but that one of those mysterious bursts of fire followed. And the krauts issued orders strictly forbidding civilian movement in the forests.

Chance words dropped by the Germans, unguarded bursts of wrath from officers of the staff billeted in the village, plus the evidence of their own eyes and ears, gradually were pieced together by the Maraites and their neighbors. In a community like Meyerode the grapevine travels fast. Most of the burghers knew of the Americans who had stayed at the Maraite dwelling. Sepp Dietrich himself, quartered in the home of Jean Pauels, the burgomaster - a relative of Anna Maria Maraite - began to thunder about American "criminal scoundrels and bandits." The krauts were getting nervous, itchy. Daily, wounded men came in from the easterly woods, some hobbling, some carried. Kraut orderlies gossiped. "Damned bandits," it seemed, flitted like ghosts through the trees out there, hid in snow banks. A German traveling those woods never knew when a bullet might come singing his way. Larger and larger detachments were assigned to guard working parties who from time to time took a six horse snowplow out to clear those wood roads. Searching patrols went daily into the forest, but no American prisoners ever were brought back.

So the weeks rolled on, with the daily crack of small arms on the winter air, and the burghers of Meyerode built up their theory. They conjectured that out in the forest a small but organized group of Americans roamed. They had plenty of arms, they had at least one medium mortar, and they were taking a steady toll of the Germans. And all the stories added up one way: that these American guerrillas were led by the young officer who had visited the Maraites, a man "very big and powerful of body and brave of spirit." He kept his wolf pack going, it was said, by sheer will power. There could not have been many of them - the Meyerode woodsmen later found no evidences of large bivouacs other than those known to be German. How they existed through those bone chilling winter weeks no one knows. Probably horse meat was their diet - there were several horse drawn kraut artillery units in the neighborhood, and horse drawn transport was daily passing through. Perhaps the Americans found rations in abandoned dumps. There was an ammunition dump at a trail crossing just a mile south of Meyerode where, after the Germans had gone, villagers found quantities of mortar ammunition still remaining.

Anyway, the daily firing in the woods continued until the middle of January. It was stilled just a few days before the counterattack ebbed and the Americans began slashing back into the neighborhood - perhaps about January twenty-second. When the Germans left, the people of Meyerode combed those woods. The burgomaster first sent two competent woodsmen - his cousin August Pauels and Servatius Maraite - to search. They found German graves and some unburied German dead. And they found a few American dead, also unburied. In a dense thicket southeast of Meyerode, not far from the six way trail crossing, Servatius Maraite found the body of an American officer, a big young man, "with single silver bars on his shoulders." Near him lay the bodies of seven German soldiers. All had been dead about the same length of time - as well as could be judged, perhaps ten days before the Germans were driven out. American Graves Registration people later would fix the date as probably January twenty-second. That no living Germans had later visited this spot, the villagers agree. This was evidenced by the fact that the American officer still had in his clothing his papers and 4000 Belgian francs, a sum no kraut looter would overlook. So the American had died as he had lived -- a free man, taking with him when he went the last of his pursuers.

That American officer, Graves Registration attests, was 1st Lt. Eric F. Wood, Jr. And the people of Meyerode say that he was the man befriended by Peter Maraite and his family - the leader of the American guerrillas, whose description by wounded Germans, according to Burgomaster Jean Pauels, fits "like a police description" with that of Eric Wood. Records and statements of eyewitnesses prove that the only officer of the 106th Infantry Division unaccounted for from December sixteenth onward - that is, neither dead nor alive as free man or prisoner of war - was 1st Lt. Eric F. Wood, Jr.

("The details of the killing of the German tanks were updated from actual accounts (1999) of those that participated in the battle at the time. The additions of these actual accounts do not change the overall description of the original author.")

MBV: Consider the difference one indomitable man made in this battle --

The three guns he saved (the only ones of his division that made it out) were critical in the "Battle for Parker's Crossroads," a delaying action on the northern shoulder of the Bulge that allowed the 82nd Airborne and other units to defend the Elsenborn Ridge. Unable to break out to the north or the south, the Germans were channeled into the delaying actions at St. Vith and Bastogne. With the holding of the shoulders, the German offensive was doomed.

Second, we can only speculate what effect his little guerrilla war had on German logistics, but if the Belgian witnesses are correct, it was enough to make Sepp Dietrich half-crazy with frustration. Of course, it was poor logistics that, as much as being channeled between the shoulders, was the reason the offensive failed.

Finally, there is the butcher's bill reckoning of the effectiveness of a soldier. How many Germans did he kill before he went down outside Meyerode? Whatever it was, it was a uneven trade for the Germans.

So take a few moments and ponder the incredible fight and sacrifice of Lt. Eric Fisher Wood, Jr. His story is an American inspiration for the ages. We are coming into another dark moment of American history. Let us hope the next Eric Woods are getting ready for the fight.