Six years ago, I first wrote on the subject, A Missed Anniversary: "Vous les Americains Sont Pires que les Francais." I present it here without changes. It is a memory of which I am not proud, but I wouldn't be who I am today, doing what I do, without the shame and regret it brought me.

29 April 1975

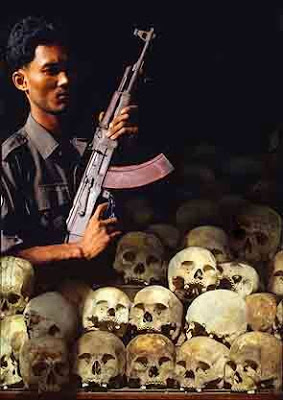

29 April 1975April is a month of bittersweet anniversaries. 19 April of course marks Lexington and Concord, the Warsaw Ghetto, Waco, Oklahoma City, and in certain drunken ATF debaucheries, the birthday of their patron saint, Elliott Ness. The picture above marks another event, the fall of Saigon in 1975. This photo was taken 29 April. Saigon fell the next day on the 30th. Phnom Penh, Cambodia had fallen about two weeks before.

I missed marking this anniversary this year. I don't know why. The memories always hang heavy on my heart. This is not merely because it was hardly my country's finest hour, but because I bear personal guilt for it. You see, as the NVA gradually overran South Vietnam and the Khmer Rouge overran Camodia, I cheered the fall of every province, marking them on a map. This was during my Benedict Arnold period, when I was a communist and an avowed enemy of the constitutional republic of the United States. As a member first of the peacenik anti-war movement which I joined in 1967, then later the Students for Democratic Society, the Young Socialist Alliance, the Socialist Workers Party, the Workers Action Movement and finally the Maoist Progressive Labor Party, I had demonstrated, leafleted, marched, rioted, been tear gassed, billy clubbed and briefly, arrested (but later released without charges), eight years of street-level radicalism, all with an eye toward this day.

Toward the end, I became a member of the PLP's "secret party," dropped from public view and on instructions began to organize a "worker's militia" in central Ohio. We'd start out vetting new members by having them break into National Guard armory parking lots and slash vehicle tires. In the end, we'd rob dope dealers to raise the money to buy weapons, all kinds of weapons. We were very good at what we did. And very, very lucky. Don't believe me? Most of my "Benedict Arnold" period papers are part of a collection at the Ohio Historical Society. Look it up. You can look up the statute of limitations too. Nobody died. Like I said, we were very, very lucky.

So when Cambodia and South Vietnam fell, I was one of the happiest traitorous bastards around. I just hoped "the Revolution" would start here in my lifetime. Yeah, I was that stupid.

I suppose I would have continued on being terminally stupid until I became stupidly dead, if it hadn't been for a kindly old ex-Wehrmacht surgeon named Richter who, at the end of his life, decided to wrestle the devil for my soul.

My day job, when I wasn't buying or stealing guns for the communists, was as a hospital aide at University Hospital in Columbus, Ohio. I was on my first marriage, then, though my son Matt had not yet been born. Richter (I am ashamed to say that at this remove I am not even absolutely certain that was his real last name -- I always addressed him as "Herr Doktor" and what few papers, reading lists and so that he had given me were apparently discarded during the split with my ex-wife) was a patient of mine, come to OSU to get a second opinion from an American neurosurgeon he trusted.

It was the two weeks between Christmas, 1976, and the New Year, 1977 that this occurred. Nothing much happened over the holidays, and here he was, stuck in another country, far from the Germany he loved. I wonder now if he saved me because he was bored and had nothing better to do. He knew that I needed saving because he was a major fan of the United States system, which had just that year seen its bicentennial. That was the question that he posed to me first, I know.

"What," Herr Doktor asked in that slightly accented and very precise English that he spoke, "did you think of the 200th anniversay of your independence?" He always had this half-smile, but with a professorial air that demanded manners. I had a Czech refugee for a history professor once before (1971) who had the same mein. Like Vlad Steffel, Herr Doktor commanded respect.

I blew him off, though, with a stupidly shallow answer about America as a force for evil in the world which would, I was sure, soon be turned back by the forces of, I probably used the commie term "people's war." Herr Doktor was mildly amused and offered to dissuade me of that theory if I would just show him the courtesy of reading some books and articles and discussing them with him during and after my shifts. I agreed. It was the unintentionally smartest thing I ever did in my life.

We began with The Road to Serfdom by Hayek. I have always been a quick reader, but my mind rebelled at the points where Hayek's analysis diverged from my own adopted dialectical materialism, which is to say, everywhere. The first time I tangled with Herr Doktor was in the cherished notion I had that it was Soviet Communism that defeated the Nazis. The Communists were the real heroes of World War II, didn't he know that?

Herr Doktor brought me up short with the observation that he had seen that conflict up close and I was dead wrong. For two days, I think, we went back over the events of his life. His German Catholic family, always doctors or academics for hundreds of years. The decadent Weimar Republic, the street fighting, the longing for order, Hitler's rise, the early clashes between the Nazi Party and the Catholic Church, the sellout of the German Catholics by the Pope, how he missed the Hitler Jugend because of his age but was impressed into the Wehrmacht as a surgeon in 1939, all of these were mere prelude to his vivid description of the tragedy of millions of young men dying in the snow, killing each other for two sides of the same collectivist coin. His escape from Stalingrad on one of the last Junkers to leave the kessel. The crimes of the Nazis. The crimes of the Soviets, and later of the East German communists. "Two parties, same faces," he pointed out. Any Nazi who wanted to live in the new system had merely to declare his conversion to Marx, Lenin and Stalin and become what Eric Hoffer dubbed a "true believer." Hoffer was another title Herr Doktor recommended.

We got fairly well along in my conversion before he left to go home to Germany to die. It was ironic that it took a foreigner to teach me how little I really knew about my own country's history. I dove into his reading list, putting it together with things in the press, things I'd observed, first as a radical then as a communist. This wasn't trading one commissar for another gauleiter or vice versa. It was becoming educated in the Anglo-American concepts of individual liberty, property, commerce and polity. It was being reminded of the Judaeo-Christian roots of all of it. It was from Richter that I realized first that while a man cannot choose the time he lives in, he can choose how he lives up to that time. And yes, Herr Doktor's reading list included Rand, Locke, Adam Smith, Tolkein and C.S. Lewis.

No one analysis fit the reality of the world, said the Doktor, you must evaluate the facts and the truth, which is sometimes unsupportable by mere facts, and make your own judgments.

The sum total of what Herr Doktor taught me subverted completely my belief in communism, which from my own experiences had become somewhat cynical and jaded anyway. I handed off my assignment and, more's the pity, the arms dumps, to my second in command. If I hadn't he probably would have killed me. He wanted to anyway, me being a traitor to the class struggle and all. (That, plus the fact that I had in my head enough evidence to send about six men and three women to federal prison for a very long time.)

Of course I didn't tell them that this was because I had a crisis of conscience. I lied and told them I was just burnt out and that my wife was about to divorce me. This was more or less true, but still a lie. However, the first thing you're taught when you get to be a killer tomato (red thru and thru) is that it is OK to lie to anybody about anything if it advances the party's goals. So given that, lying to liars was even expected, in a way.

Anyway, I got out and never looked back. That didn't mean I wasn't constantly haunted by the reality of what I had done.

Chieu Hoi and Hoi Chanh.

Chieu Hoi and Hoi Chanh.Flip back up to that first image above, the evacuation of the American embassy in Saigon. Consider the awful reality of two countries left to people who were hardly little Jeffersonian democrats, and who set about proving that in the worst possible ways after our choppers had gone.

I once did a radio show with Dr. Russ Fine, who then had the evening call-in show on a certain station here in Birmingham. David Horowitz' book Radical Son had just come out, about his conversion from being a red diaper baby into a real American. David was pimping his book and Russ was happy to talk about it and to have someone experienced from that period of history to chat with Horowitz as someone with similar background.

After exchanging bona fides about the extent of our previous sins, I asked him the question that had, since my encounter with Herr Doktor Richter, most preyed on my own mind:

"David," I asked, "do you ever feel Benedict Arnold looking over your shoulder?" He was quiet for a moment, you could hear the slight crackle of that long phone line to California. Then he said, slowly, solemnly, "Yes."

"But if you're like me, you'll never get caught on the wrong side of your faith or the Constitution again, will you?"

"No," he replied firmly, "I won't."

"Chieu Hoi," I replied, "Hoi Chanh."

David understood the reference.

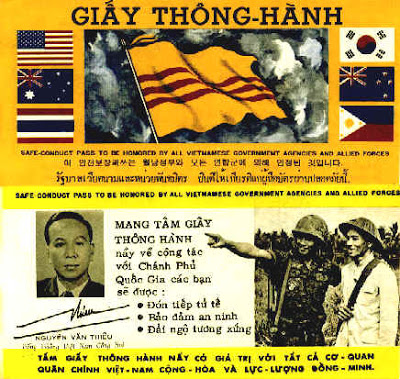

Chieu Hoi means "open arms" in Vietnamese, the name of a program designed to recruit ex-communists to the South's anti-communist fight. Someone who entered the Chieu Hoi program became a Hoi Chanh, a returnee. In Vietnam, many became Kit Carson scouts and worked alongside American and South Vietnamese troops.

And believe me, there is no greater anti-communist than an ex-communist. We know all the lies, first hand.

We also know that we can't go back.

We have burned our bridges and will live or die on the ground we have chosen. Of course twelve-step ex-leftists like Horowitz and me aren't brave at all compared to the Kit Carsons, nor did we recant in the expectation that we were joining a losing side like George Orwell or Whittaker Chambers. THOSE guys changed sides in the belief that while it was the right thing to do, they were probably joining a losing cause. Both were under the impression that either Sovietism or fascism was going to win in the end. But still they denounced the lies and stood on the truth, expecting death at the wall or in a ditch rather than reward. (Orwell's Homage to Catalonia and Chambers' Witness were both on Herr Doktor's list.)

And one other thing. As near as I can tell without a god-like glimpse into other men's souls we are all, we ex-communists, motivated by guilt at what we did in the name of totalitarianism. This guilt we must expunge by our every action for the rest of our lives. We cannot backslide, we cannot be fooled, or fool ouselves, into believing the lies ever again.

Don't believe me? Let me give you an example of the depth of my own guilt, something I am reminded of often, but particularly on anniversary days in April.

"Vous les Americains Sont Pires que les Francais."

"Vous les Americains Sont Pires que les Francais" is the title of Chapter 27 of Never Fight Fair!, an oral history of the SEALS by Orr Kelly. Chapter 27 is a reminiscence of William G. "Chip" Beck, who served as an advisor with the Cambodian Army as it fought a desperate battle against the Khmer Rouge rebels from January 1974 until that fatful April 1975. Beck tells the story of the heroic resistance of the anti-communist Cambodians and especially of one man, Khy Hak who most exemplified and personified that resistance. An excerpt:

I was an advisor to the 11th Cambodian Brigade at the time. I was the only American in Kompong Thom, this little town in central Cambodia. There were two other foreignrs there -- a Norwegian doctor and a French priest. He had been there twenty-eight years and spoke Cambodian like a native. We used to call his congregation "the Christian soldiers." After he said Mass, he would go out and show them how to put up a machinegun emplacement with effective cross fire.

I had responsibility for an area between Kompong Thom and siem Reap, where Ankgor Wat is. I used to travel back and forth in that whole northern area.

I started out based in Siem Reap but I was so impressed by the quality of the officers and what they were doing with the men in Kompong Thom that I went back to the embassy and told them they needed a full timer down there with the 11th Cambodian Brigade. They agreed.

The provincial governor was also a general whose name was Teap Ben. He was the political provincial advisor and senior military person. The man in charge of most of the combat forces was Col. Khy Hak, probably one of the two military geniuses I have met in my life. The guy didn't go to school until he was eleven years old and ended up completing the national military academy at age eighteen at the top of his class.

Khy Hak had studied everything from Napoleon to Mao Tse Tung. In his library I found these huge books on the Napoleonic battles. There were maps where he had drawn in red and blue where the troops had gone and where they had made their mistakes. He could think in strategic terms. He could send massive troop units going out but also have his men infiltrate into the Khmer Rouge as guerrillas. He could fight as a guerrilla or a major tactician.

When the war started, these two guys were at Siem Reap, a little outpost. They were maybe a major and a captain at the time. That became one of the few places where, when the North Vietnamese and the Khmer Rouge started running over Cambodia, they didn't get very far. They were not guys who sat in there offices and worried about their next corruption deal. They would go out and fight with the troops.

Khy Hak got wounded, for the first time in his life, during the battle for Ankgor Wat. Instead of being evacuated, he had his men put him on a door amd carry him into battle while he was still bleeding. It was an incredible battle because Khy Hak has a sense of history. He didn't want to use heavy artillery to take out the North Vietnamese because he was afraid of destroying the historic ruins of Ankgor wat. So he had his men go in and fight hand to hand, tactical, down and dirty.

Kompomg Thom had been overrun and almost taken by the Khmer Rouge in 1973, the year before I got there, and when they sent Teap Ben and Khy Hak, literally, the Khmer Rouge were in downtown Kompong Thom. The helicopter flew these two guys in, wouldn't even land, as the troops were fighting to get back into the city. Literally, they retook the city house by house.

By the time I got there, the Khmer Rouge were still surrounding the town and attacking it, if not every day, every week. I was just so impressed by what was going on I decided to make my own headquarters there. The longer I stayed and saw what they were doing, the more impressed I got.

At one point in the dry season, Khy Hak had had enough of being surrounded by the Khmer Rouge and said he was going to take back the territory beyond the town perimeter. . . Khy Hak decided he and his brigade, under cover of darkness, would walk out of Kompong Thom along Highway 5 and wreak havoc among the Khmer Rouge. And they did. In the course of three days they walked a hundred miles and they brought back 10,000 people from among the Cambodian population. By the time a month and a half was finished, they had brought back 45,000 people from the communist zone, brought them back into a little town that previously had only 15,000 people in it.

When Khy Hak went out there, he didn't force the people to come back at gunpoint. He would get up on a tree stump or a chair and talk to the villagers.

He told them, "Look, there's corruption in the government, there's corruption in the army. But if you come back I will try to protect you. The Khmer Rouge willl try to stop you from going. I will help you get back. Once you reach safety in Kompong Thom, they will try to attack us and kill you. I will try to protect you. It's going to be hard to feed you. You will have to grow your own crops. We can't count on anybody but ourselves. But you know what it's like out here under the comminists. Choose. Make your choice."

And they made their choice, by the thousands.

I flew out in a chopper after the operation got going and I couldn't believe my eyes. . . I stayed out there with troops for three days. I really wasn;t supposed to but Khy Hak challenged me, "How do you know that I won't lie to you? Or someone will ask you if I'm lying. See for yourself. You can tell them the truth." so I stayed there . . . As Khy Hak had predicted, the more refugees we got into the town, the more of a political embarrassment it was for the Khmer Rouge. They intensified the pressure on Kompong Thom in March and April of 1974. . .

(Short of rice for the refugees and unable to get enough from USAID, Khy Hak staged a raid out into the countryside)

. . . in an area where the Khmer Rouge had been stockpiling rice they had taken from farmers. . . As we were pulling out, some mortar rounds started falling. Khy Hak got on the radio -- the Khmer Rouge had the same radios he had -- and issued a challenge: "This is Col. Khy Hak. Here is my precise position. I will wait here for one hour. There is no need for you to shoot at unarmed civilians who can't defend themselves. If you want to fight somebody, fight me. I will wait. If you are not here in an hour, I will figure you are too afraid to do it."

They didn't come. . .

(Beck tells the story of the bloody and heroic defense of Kompong Thom against overwhelming numbers of Khmer Rouge.)

The day the seige of Kompong Thom was broken, with three hundred Khmer Rouge left dead on the battlefield, the headlines in the world press, one major newspaper -- I can't remember which one -- said: "Rebel rockets hit Phnom Penh; Three Killed."

These defenders had killed three hundred to one thousand enemy soldiers in bloody combat but there was never a story told about this.

For the rest of the dry season, things were pretty calm there. Khy Hak was promoted to general the final year, in 1975, in the final months in Phnom Penh.

He and I had worked out a plan where I would take his wife and children and set them up on an escape route I had set up in northern Cambodia for the civilians.

I didn't know when Operation Eagle Pull (the American evacuation) was going to go. When I found out, I was several hundred miles away from his family. I couldn't get to them directly. I had somebody else go over to the house to ask Mrs. Khy Hak to leave with them. She refused. She didn't know her husband wanted her to leave.

By the time he was able to get back to Phnom Penh, to the center of town as the perimeter was falling, there was no way to get her out. He put his wife and his five children -- beauitful little children, from four years old to eight -- in a jeep. The Khmer Rouge caught them approaching the airport and took them over to a pagoda.

One of my Cambodian soldiers who went back in and talked to witnesses said they killed the little kids. They executed the children, then they shot his wife. After making him witness that, they executed him. So they got their revenge on him.

Chip Beck's sketch of General Khy Hak.

Chip Beck's sketch of General Khy Hak.

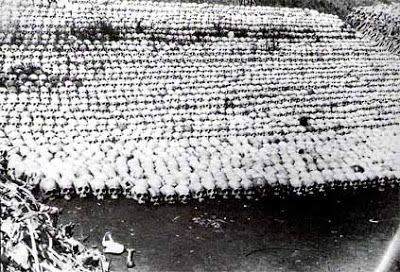

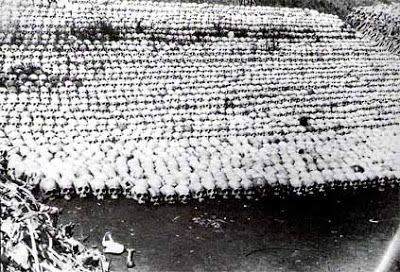

We then started hearing of many atrocities being committed. (After Phnom Penh fell to the Khmer Rouge on 16 April 1975, as many as four million Cambodians were slain by the victors over the next two years.) The Khmer Rouge would get on the single sideband radios that had been part of the military network. After the Americans had made the evacuation in Eagle Pull, the Khmer Rouge would get on the radio and hold the key so you could hear the office people being tortured and murdered on the air. . .

Unlike Vietnam, the Cambodians could have held out. We, the advisors, were told we could supply the Cambodian army as long as they could fight. That's what we told them. After we evacuated the country, that order was rescinded.

The French died at Dien Bien Phu. They were soundly defeated but they fought and we just went out the back door.

We, the advisors who had lived with these people, sometimes for years, had to sit there and listn to them on the radio calling to us, saying, "Where are our supplies? We're still fighting. We're holding out."

Finally they ran out of ammunition. That's the only thing that made many of these people surrender and then they were executed by the Khmer Rouge.

One of the last transmissions -- the last transmission I ever heard out of Cambodia -- was a Cambodian colonel, just before they killed him. You could hear them breaking down the door. You could hear him say, "Vous les Americains Sont Pires que les Francais." -- you Americans are worse than the French.

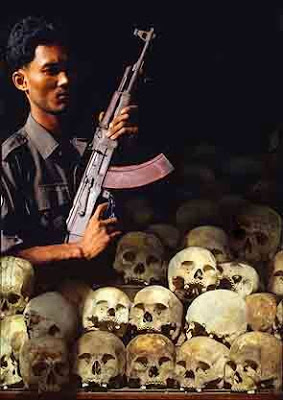

Recovering your conscience too late.Yes, we were. And I was among the worst. I CHEERED the murderers on. I did my best to make THIS happen.

And THIS.

.jpg)

And THIS.

Do you begin to understand the guilt for someone who has recovered his conscience too late? The blood of Khy Hak's family is on my hands, just as the blood of Russian kulaks was on Whittaker Chambers' hands. When you recover your conscience, the only thing you can do is make sure, to the best of your ability, that it never happens again.

We do not choose the circumstances of the world we live in, yet we must react as best we can to its challenges. For me, I have no choice. I must continue to walk along the path Herr Doktor Richter showed me more than thirty years ago in that hospital room on Nine East. My fate was set, and my Master selected, when I turned my face from pagan collectivist evil under the patient tutelage of a wise, slight-statured old man with a perpetual smile and white hair.

I can never and will never go back.

So when somebody whispers in your ear, "Well, you can't trust him, he used to be a communist," think twice. For he may be the only one who sees clearly enough to point your way through the minefield of bad choices that collectivism -- any and all collectivism -- represents.

And when I cross over to that place my Master has chosen for me, I can only hope Khy Hak is there, so I can finally beg his forgiveness for the sins of my youth. Until then, I will think of him and the millions like him every April, when spring reminds me of my guilty complicity in collectivist mass murder.

.jpg)

Hundred Head

Hundred Head