Gabriel and the Spooky Owl. (A Christmas story for my grandsons.)

(NOTE: I would like to give a tip of the boonie hat and deep genuflection to Alabama Division of Wildlife biologist John S. Powers who wrote this article about owls which appeared in a January 2011 copy of The Trussville Tribune and to my grandson Gabriel, who first told me by phone the story of his own encounter with a spooky old owl outside his house in Germany. Together they gave me the idea and the factual structure around which I built this story.)

Gabriel and the Spooky Owl, by Mike Vanderboegh.

Dedicated to both my grandsons Mason and Gabriel Vanderboegh, half-brothers, perhaps, but each all Vanderboegh. If Mason is not in this story it is not because I don't think of him and miss him daily.

The first thing you should know is that there was a war. It doesn't matter which war, or when, not really, not to this story anyway. It was the war that Gabriel's daddy had to fight in, so after he went away to the army, Gabriel and his mother moved back to her parents' farm in north Alabama. Gabriel's granddaddy lived way back up in the hills, in a converted dogtrot cabin. They called it a "dogtrot" because it had been built when there were still unfriendly Indians roaming around and the safest cabin to build was actually two square ones made of big square-cut logs and no windows downstairs, just stout doors that could be barred, and an open porch that connected the two squares and an upper story that spanned the two. (If you think about it, if all you have is for construction is a cross-cut saw, a hatchet, an axe and maybe an augur for boring hole for the wooden pegs to hold the smaller pieces together, it is a lot easier to build two stout log squares with a space in between them and then connect them bottom and top.)

The dogtrot was really designed to be a little fort. With no windows down below, the settlers would cut firing slits in the logs so they could fire through and each lower square could support the other with fire from flintlock rifles if somebody tried to break down the door of the other. The stairs to the upper level were internal to the rooms so nobody could get in the top part of the house without going through the lower and each stair ended at another stout door with firing slits on the other side. They even cut removable firing ports in the oak plank floors of the upper story which covered the stairs, so that even if an enemy got inside one of the lower squares, they could still be shot at by people defending the upper rooms. In the upper story, then, were the only windows in the house and even these had stout shutters with firing slits that could be pulled shut in case of attack. The thick logs and oak planks were well-nigh bulletproof to the weapons of the day.

I know, I know, I'm getting to the dogtrot part. Anyway, with a big open porch below, between the two lower squares, you could sit in a rocking chair out of the hot Alabama sun of a summer and stay cool in the shade. Of course, it being open and all, the dogs would also shelter there, and could run from the front to the back without encountering a door, so it got the name of "dogtrot."

After the Trail of Tears, when the federal government had forcibly removed the Cherokees, Upper Creeks and Chickasaws from the state, adjoining rooms and a cookhouse had been built on out back and other windows and doors had been cut in the thick logs to make the living arrangements cooler and more convenient and the logs had been covered over inside with nicer looking boards. But Gabriel, being just six years old at the time, didn't know any of this. He just knew that this was his grandpa and grandma's house and it wasn't as nice as his own home. It also smelled funny and he didn't like it.

John Looney Pioneer House Museum, a dogtrot cabin near present-day Ashville, Alabama, built about 1820.

But I had to tell you all of that to explain how it was that Gabriel came to have one of the upper rooms with a window, for that was how he met the spooky owl.

For starters, Gabriel didn't like his room because it was high up the steep stairs, which were difficult for him to climb, and once he was upstairs he couldn't hear a thing downstairs from the add-on room where his grandma and grandpa lived, nor could he hear the familiar sounds of his mother who lived in the room down below him. Gabriel's momma took the lower room because she was about to have a baby and she couldn't take walking up and down the stairs. Gabriel was, then, all alone upstairs and quite cut off from all the people who made life familiar and comforting. Even the fireplace at the end of the room had its own plaster ductwork up through the brick chimney, so he didn't even have the ability to listen downstairs, for chimneys make remarkably good stethoscopes, you know.

But Gabriel didn't have a chimney for a stethoscope.

He really was quite alone at night, and, like most young boys and girls, the night scared him.

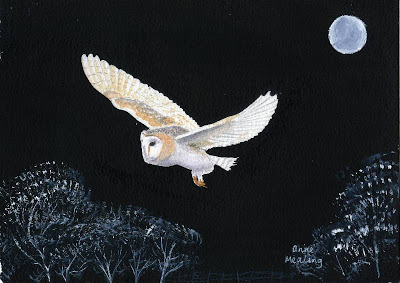

Actually, though, he wasn't quite ALONE alone. For almost every night there was an old barn owl which perched on a tree branch right outside his window.

The owl scared Gabriel much more than the dark. It scared him, way down deep, where strange and mysterious things often reach, especially when you're young. Especially when they are armed with sharp talons and sharper beaks. Especially when they make shrieking, scary noises and seem to look right through you.

Of course, Gabriel wasn't the first human being, child or adult, who had been scared by an owl. Cavemen drew vivid pictures of owls deep in European caves, and even after people emerged from caves and began building houses outside, owls were feared and avoided. Some people thought owls were emissaries of the devil and that they brought bad tidings and death. Others thought that they actually were wise messengers from God and were lucky. The ancient Greeks believed the owl to be a bird of wisdom, an idea which continues today. The Indians who lived in Alabama long before any white people thought them to be messengers to tribal shamans, who could, if they were themselves wise, interpret what The People should do. (All the various tribes had a word for themselves. Each called their own tribe "The People" in various languages and dialects and other tribes "The Others." It wasn't until the Europeans came to America that they discovered that were "Others" stranger than the "Others" that they were familiar with, but that is another story.)

Cherokee shamans considered owls to be particularly valuable consultants for all important tribal decisions. Some Indians believed owls were responsible for guiding the souls of the dead safely to the afterlife and still others fletched their arrows with owl feathers so that they would fly silently, like the owls themselves.

(It wasn't true of course, owls make as much noise flapping their wings as any other big bird. But when an owl strikes, it generally leaves its perch by extending its wings quietly and falling in flight, gliding silently in on the target it wants to kill and eat, so maybe it was this last part of the owls' movements that made the Indians believe in the silence of owl fletching. Or maybe it was just good marketing on the part of some ancient Indian who specialized in gathering owl feathers. One guess is as good as another, as Gabriel's grandpa always said.)

Now a lot of people think that all owls hoot, or say, "Who!" "Who!" A lot of them do. But not the barn owl. The barn owl has a shriek like a banshee, the mythical creature from Irish folklore, who was said to start out in a keening moan and to shift to a shriek if she was ignored. Gabriel's grandfather knew all about banshees, or so it seemed, for he occasionally told ghost stories about the women of the fairy mounds and how back in the "Old Country" they were thought to be an omen of death, occasionally being seen washing the blood stained armor of some brave knight about to die.

Grandpa loved to tell such stories, and the more they scared Gabriel, the more Grandpa seemed to like them. Gabriel didn't like them, but that didn't seem to bother Grandpa. And when Gabriel would cry out in fear, Grandpa would say, "Well, if you don't believe me, ask your Grandma, her people believe in banshees too." Grandma was mostly Cherokee, and she would always nod solemnly to Gabriel and beckon him to come to her and she would always wipe his tears with her apron that she always wore and fold him in her arms as if to say, "I won't let the banshee get you, Gabriel," which was more words than Gabriel had ever heard her speak at one time because, as Grandpa explained, "Cherokees ain't much fer talkin'," which Grandpa more than made up for, him being Scotch-Irish, as he said. What Scotch-Irish meant, Gabriel was a bit uncertain, but mostly it seemed to mean that every now and then Grandpa drank entirely too much "popskull" and that drunk or sober he talked ALL the time. If that's what Scotch-Irish meant, then Gabriel was prepared to believe that Grandpa was the most Scotch-Irish man he knew. But in Gabriel's mind, his Grandma's largely silent love didn't much make up for the fact that if there WERE banshees then one might end up getting HIM some night.

And so it was that very first night that Gabriel slept in the upstairs room of the old dogtrot cabin, he found he couldn't sleep, tossing and turning and worrying about banshees and possibly more horrible creatures out there in the dark north Alabama hills, just past the window pane, against which the fingers of the tree tapped, tapped and tapped again with the wind.

In fact, Gabriel was quite awake when the old barn owl announced itself with keening, sustained screech, just outside the window. It was ear-shattering. It was frightening beyond all reason and belief in God Almighty. It was, Gabriel was certain, the bloody-handed banshee come to take his soul.

And Gabriel screamed right along with the owl that he thought was a banshee. In fact, he screamed so loud that he frightened the owl away from the window and off it went, flapping and shrieking so Gabriel never saw it that first night.

In fact, he didn't see much of anything that night because after that he was hiding under the covers. And he didn't go to sleep for a long, long time until his fear and exhaustion came and took him finally from waking to terrible nightmares of the banshee coming to get him. (Downstairs, Gabriel's muffled scream caused his tired mother to turn over in the old fashioned rope-bed, her sleep bothered but not interrupted. On the backside of the house, Grandma and Grandpa slept on too. Accustomed to the chorus of familiar night sounds of the farm, of which the barn owl's shriek was quite a frequent contributor, they didn't even stir.

The next morning Gabriel found his mother in the kitchen, peeling and slicing potatoes to fry, and he interrupted her work to tell her that a banshee had been at his window the night before and could he please, please, sleep with her that night? Grandma was fixing bacon and eggs for breakfast at the cast iron stove across the big room, and stopped her toil long enough to turn around and deliver a regular oration on the subject of Gabriel's bad night: "Jest a barn owl."

Now I'm not sure if Calvin Coolidge had been born yet when this story takes place, but it was for sure and certain that Grandma could have given "Silent Cal" lessons.

For her part, his mother just nodded her head to Grandma, who turned back to her skillets, eggs and bacon, and then gently her daughter started to explain to Gabriel about barn owls. Gabriel, with that unearthly shriek still sounding in his head, didn't believe a word of it. Nothing that loud and scary could have had corporeal form. It MUST have been a banshee.

Gabriel's mother saw that she wasn't getting through to the boy, but said she'd have Grandpa explain about barn owls later. One thing was clear though, Gabriel was not getting out of his lonely prison upstairs. He was a "big boy" now and would have to figure out how big boys were supposed to act. Gabriel thought that if being a big boy meant getting carried off by a banshee, he was sure he wanted to stay little for a long, long time.

That night, he trudged up the stairs to his smelly, musty old room as reluctantly as a condemned Fenian mounting the King's gallows back in the "old Country." (Gabriel didn't know what a Fenian was either, although they often figured prominently in his Grandpa's stories. Mostly they seemed to end up getting mysteriously but consistently hanged all the time, which didn't seem to Gabriel to be an occupation with much of a future.)

That night, neither the barn owl nor a banshee showed up on the branch outside his window and Gabriel, being exhausted from the previous night, fell almost instantly asleep and slept like a baby. For his part, Grandpa had been working all day and into the night with the harvest and so had not had a chance to explain to Gabriel about barn owls, although he did make a banshee joke at supper, with a big smile and a wink for Gabriel, who didn't find any of it the least bit funny. But on the third night, by the light of the full moon, the barn owl came back.

It announced its arrival with a regular "THUMP!" on the side of the cabin wall just to the right of the window, as the branch gave way to the owl's considerable bulk upon landing and smacked up against the thick structure. Gabriel, who was just on the verge of sleep, instantly came awake and sat bolt upright in the bed, all his sense straining.

Outside the window, through the simple cotton curtains, he could see something, something ANIMATE, shifting about on the branch. It was the owl, and he was hungry. Now something happened that readers may not credit because in the story thus far we have highlighted Gabriel's very real fears. But the truth of the matter was that Gabriel really was quite a brave little boy, and he was also quite curious. Gabriel also knew a couple of things, because since the unearthly shriek he had done a lot of thinking about banshees. In none of Grandpa's stories about the banshees did they go "THUMP!" They screamed, they keened, they moaned, they shrieked, sometimes they washed armor, but they didn't thump.

Secondly, if all a banshee was was some kind of noisy ghost then walls wouldn't stop them. Other ghosts Grandpa had told him about could walk through walls, so why would a wall stop a banshee? (This was actually something Gabriel had worried quite a bit about in the past 48 hours, that the banshee just might come right through the wall and snatch his soul off to Hell. Gabriel knew about Hell. His momma had explained it to him, and they read the Bible often in the morning and before bed. Not only that, but the Baptist preacher at the camp meetings knew an awful lot about Hell, and he alone, of all the other adults Gabriel knew, was almost as long-winded as Grandpa. When he got going about Hell, he could go on for hours. So, yes, Gabriel knew about Hell.)

Armed with this logic, Gabriel's curiosity overcame his fear. Very slowly, he pulled back the covers and swung his feet over the side of the bed. The floor was cold, it always was, and it threw a shiver up the entire length of his body. But it was not, Gabriel realized, fear. (Gabriel was also very bright, did I tell you that?) Anyway, he eased over to the curtains and peeked out. There, illuminated by the moonlight, was the most striking, amazing, impossible and scary thing Gabriel had ever seen, up close or far away.

Now a barn owl is a pale, long-winged, long-legged owl with a short, sort of square tail. This one was a humdinger of a big barn owl too. He was pushing two feet in length and had a wingspan of twice that. Its face was heart-shaped and brilliant white in the moonlight, and it had the most piercing black eyes Gabriel had ever seen or would see later in life, and he lived to a ripe old age. The ridge of feathers above the beak resembled a long nose. What wasn't white was a fine, rich brown that gave way to pearly white, mottled with speckles of brown and black. The bill of the owl, which had vivisected with precision so many mice, rats, chipmunks and other rodents, was a luminescent hard-edged white and its talons, which snared the victims all, were by contrast jet black.

Gabriel was mesmerized. His logic had taken him to the window and his logic had been right. This was no banshee. This was the most magnificent bird he had ever seen. Then the owl did something even more startling. Totally ignoring Gabriel's face in the window, it let go of the branch and glided away, flashing by the light of the full moon, wings fully extended, talons deployed dropping like death from above on an invisible quarry below.

Gabriel thought it was going to dive right into the ground, but at the last instant, it broke sharply as its quarry, a field mouse, zigged when it should have zagged, and the owl, deftly snatching it up, rose heavenward on great flapping wings and disappeared from sight around the cabin toward the barn across the lane. It was a demonstration of skill and power that Gabriel would remember the rest of his life.

Gabriel watched long into the night, but the owl did not come back. Finally, reluctantly, Gabriel crept back to bed, chilled through, but strangely excited and happy.

For one thing, Gabriel concluded, the banshee would not be coming to steal his soul down to Hell. Not just yet, anyway.

After that, Gabriel sought out his Grandpa to find out more about the barn owl and his kind. Grandpa knew the owl as an old friend knows another, he said to Gabriel's surprise. Grandpa explained how farmers liked to have barn owls around to keep down on the rats and mice around the farm, because those vermin not only can eat the farmer's crops in storage but also foul the rest that they leave behind with their droppings. Plus, said Grandpa, "they're filthy critters what brings disease."

Grandpa told Gabriel about how a barn owl will sometimes hiss like a snake to scare away intruders, and when captured or cornered by something bigger than themselves, how they throw themselves on their backs and flail around with their razor-sharp talons, slashing and scaring their enemy. Sometimes, Grandpa said, angry barn owls will make raspy warning and a click-snap with its bill, "jest to let you know yer about to git the business end of him."

The owl, said Grandpa, was a good friend, but a grumpy one. "Jest give him a wide berth and he'll do his job and you won't git yer nose bit off." Grandpa claimed to know someone whose nose had been bitten off by a barn owl, but when he said it he had the look in his eye that he got in his other stories just before his daughter would say, "Irish blarney." Gabriel didn't know exactly what Irish blarney was either, but he got the feeling that his momma didn't believe what his Grandpa was saying. Before his daddy had gone off to war, Gabriel had once overheard him say to his Gabriel's momma that her daddy "shoveled more manure with his mouth than anybody on God's earth." His momma had laughed, so Gabriel guessed that blarney meant the same thing as manure. I told you he was a bright boy.

Grandpa said one other thing that bothered Gabriel. The owl, he said, had been hanging around the place for more than twenty years, how many more he couldn't exactly say. The owl was surely about as old as most owls get before they die, maybe older. One day soon, Grandpa said, we'll be needing another owl, and he hoped that they'd get one as good and faithful as this one.

Anyway, after that Gabriel would study the old spooky barn owl every chance he got. It got to where the owl would look back at Gabriel through the window and not only not be startled at his presence but almost seem, well, friendly. Finally, Gabriel took to leaving the window open and one night the owl came right into the room and perched on top of the chiffarobe.

Gabriel didn't make a sound. He tried not to even breathe. Eventually, the owl, having searched the room with its night vision and finding nothing to eat, flapped away on its great wings, straight out the window, though how it timed the beat to avoid hitting the sides of the window happened so fast that later Gabriel couldn't quite figure it out.

Months passed, and the time came when the shriek no longer even startled him, and he came to consider it as just a hello from an old friend in the dark. The spooky old owl taught him how not to be afraid of the dark, too. Gabriel learned a lot from that old barn owl that fall and winter.

Then came the spring. And with the spring, came the rat.

Norwegian rats, who didn't come from Norway, in the hold of an Eighteenth Century ship.

The rat, had any human seen him before Gabriel came face to face with him, was a big, brown rat and would have been called a "Rattus norvegicus," or Norwegian rat, by any scientist of the day. This was to distinguish him and his kind from the much smaller common black rat, known to the scientists as "Rattus rattus." Why he was named a Norwegian rat by John Berkenhout, the eighteenth century English scientist who labeled his kind, remains somewhat of a mystery, since it was later determined that England was infested with such rats long before Norway and in fact they had originated in northern China. By such logic does the Transportation Safety Administration strip search Lutheran ministers from Denmark looking for jihadi bombs these days, so perhaps we shouldn't think so poorly of the judgment of John Berkenhout, even if he was a royal agent of George the Third in the American colonies during the Revolution. Although, come to think of it, Norwegian rats first appeared in America in the 1770s, so maybe Berkenhout brought them with him. Hmmm.

John Berkenhout, scientific slanderer of innocent Norwegians. He named a rat after them, even though it was found in Britain first and originally came from China.

The thing about this rat was, Norwegian or not, well . . . he was BIG. He wasn't quite as big as the giant rats of Sumatra, but he was the biggest rat Gabriel had ever seen.

Sherlock Holmes, Dr. Watson and the Giant Rats of Sumatra.

The rat had come upriver from the port of Mobile in a load of grain on a barge and wasn't discovered until the sack it was hiding in broke open at Parmenter's Store down on the Byler Road. When Gabriel came face to face with the rat on the back porch of the dogtrot cabin, it was hungry, smelled food from the kitchen, and was aggressive. It was also infected with the germ called "ratbite fever," which back then killed fully half of the people who contracted it.

The rat was in fact the closest that young Gabriel had ever come to dying up to that point in his young life. And it was ready to attack.

Gabriel began backing up, out of instinct as much as anything. Too late.

The rat leaped.

But not fast enough.

There was blur, and then a huge collision as the barn owl sank its talons into the rat at full killing speed. Together they tumbled off the porch and into the dust. For this was no field mouse, no black rat. The barn owl had picked on an enemy every bit as big in the body as it was.

It was a fair fight.

The rat's incisors were quick and powerful. Together, the owl's talons and beak were quicker and struck more deeply and surely. The rat got in one effective bite, just one, on the breast of the owl. After that, the razor beak closed on the back of the rat's neck, the talons digging deep into the haunches. Feathers and fur flew. More feathers than fur, but then there was more rat's blood in the dust. Then much more. Then too much. As the owl's beak severed the rat's spinal cord, it spasmed one final time to escape the death from above that it could no longer strike, then died.

The owl held onto the neck of the rat for some time. Maybe it was a few seconds. To Gabriel it seemed like an eternity. Then, almost gently, it released the rat and sort of . . . collected itself . . . blood running down its chest feathers, staining the white, the cream, the black and brown speckles.

Those big black eyes looked through Gabriel. Then, after a false start, the barn owl flapped away on those big wings, around the house, and seemed to be on course for the barn across the lane when Gabriel lost sight of it.

Grandpa was in the fields. Grandma and Gabriel's momma were tending his new sister inside the house. It took some time to tell them, one by one, about the fight between the rat and the owl, and to show them the rat's body.

Still, nobody, not one of them believed it, at first.

You see, the thing is, that both owls and rats are largely nocturnal -- creatures of the night. But the duel in the dust, when the owl intercepted the rat's leap toward Gabriel, happened, if Gabriel was to be believed, at just about high noon in bright daylight with the backdrop of a cloudless sky.

Grandpa, even after examining and then burying the carcass, still was skeptical. So too was Gabriel's mother. It was unheard of, an owl flying at noon.

Finally, Grandma held up her hand to silence their objections and the room fell quiet. She then gave the longest speech Gabriel ever heard her give, before or since.

She prefaced it with a question.

"Gabriel, do you know what your name means?"

No, he replied, no one had ever told him. It was just his name. It meant, well, him. What else could it mean?

"It means 'God is my strength.' In the Bible Gabriel is God's archangel, His messenger to His people."

She paused. Then she fixed Gabriel with a look at once so loving and yet commanding that he couldn't breathe.

His Grandma said, "I think that owl was God's messenger to you."

And then she smiled.

One thing was certain.

The spooky old barn owl never came back.

Gabriel never saw him again, and they never found his body.

One day, a few weeks later, Gabriel was still fretting over the loss of his friend and speculating over why he had never been able to find the owl's body.

Grandma listened for a bit, and then just held up that imperious hand. When Gabriel was silent, Grandma said, "Flew back to Heaven, I 'spect."

And those were the last words she had to say on the subject.

As he grew older, Gabriel came to believe that Grandma was probably right, as she was with most things.

13 comments:

Super story...you kept me to the very end! What a great legacy for Gabriel.

Great story. Only quibble I have is with the sentence about owls' wings making as much noise when flapped as other birds' wings. If the staff at the Carolina Raptor Center in nearby Huntersville, NC, are correct, owls'feathers are a bit "fuzzier" at the edges than other birds' wings, and thus there is a bit of a silencing effect. They even have samples of owl and hawk wings at the lecture/display area so that visitors can see for themselves, and the staff will even demonstrate the difference in sound by "flapping" the two wings for comparison. You're right about the preferred hunting technique of dropping silently down in a glide, however, although hawks and falcons will also utilize it when hunting prey on the ground.

"The first thing you should know is that there was a war. It doesn't matter which war, or when, not really, not to this story anyway. It was the war that Gabriel's daddy had to fight in, so after he went away to the army, Gabriel and his mother moved back to her parents' farm in north Alabama."

This is a deft touch.

It sets up the story of how a seemingly absent father (God) can be present through the auspices of an agent, who at the critical moment, elects to interpose himself between evil and a helpless boy.

The boy, made in his father's image, is Man; the magnificent owl who shed his blood is Jesus Christ.

"Gabriel never saw him again, and they never found his body."

He is not here, for He has risen, but His messengers are with us to this very day.

They do not always appear as owls, though. Sometimes they resemble fat old men with canes. ;^)

MALTHUS

BRAVO!!!Excellent storytelling. It Appears that you have inherited much of Gabriel's grandfather's gift of blarney. And we are the fortunate recipients. Thank you. And Merry Christmas and Happy New Year. Good health and long life to you.

B Woodman

III-per

vw: holody - close enough

Fun story - thanks for sharing!

In an attempt to be helpful, I offer the following:

"...Finally, Gabriel took to leaving the window and one night the owl came right into the room and perched on top of the chiffarobe..."

I THINK you MEANT to say "...Gabriel took to leaving the window <> and ...".

HTH!

City boy, 53 years old, first barn owl screech two years ago. Buzzed by my head screaming in the pre-dawn. Seemed the size of a 737, felt the wind.....

OMFG!

Then flew off chuckling....

Still haven't gotten my nape hairs down....

Good story, thanks Mike.

Greenman227

Thanks for such a great Christmas present Mike. God Bless!

You had me at "hello"!!! I read you everyday but have never commented before!

What a beautiful story! I am a woman..so I did cry as I read this. You are a very gifted storyteller and your children and grandchildren are very lucky!

My first thought was..you should have written this as a childs book...

Bravo! Encore.

Great story! If you are ever up in mid mich, I am at your service...

III

Mike,

C. S. Lewis would recognize you as his peer.

Thank you. You continue to amaze and inspire. We are so fortunate to have you as one of the leading voices of Liberty.

Jon III

Wonderful story!

We had a big barn owl on our farm when my sons were small. My boys shot lots of crows and other crop destroying birds, but they would never have dreamed of hurting the owl.

It used to perch on the top of the tin roof sometimes and serenade us with the owl's unique call. Then I'd tell them the Scottish ghost stories that were part of their heritage.

How wonderful to relive those memories.

It was indeed a wonderful tale, and as mentioned, it would make a splendid children's book, which would in turn add a few shekels to your meager treasury, if that would be meaningful to you.

I recall when the rather dissolute genius, Oscar Wilde, had written The Selfish Giant, he said that it was a present for all the children of the world; and of course Kipling did his fair share of stories for the young ones. So why not you?

From time to time we have an owl who stays in the trees beside the house out here, a very big fellow, and he does make a soft, mournful hoot, but as I've always loved owls, it is more a comfort than a fright.

Post a Comment