Bataan Death March survivor Bert Bank flashes a big smile Friday, Oct. 31, 2008, at a plaque with his likeness on it during his induction into the Alabama Military Hall of Honor at Marion Military Institute in Marion, Ala. Bank died Monday, June 22, at age 94.

Bataan Death March survivor Bert Bank flashes a big smile Friday, Oct. 31, 2008, at a plaque with his likeness on it during his induction into the Alabama Military Hall of Honor at Marion Military Institute in Marion, Ala. Bank died Monday, June 22, at age 94.The funeral of Bert Bank will be held today, 25 June 2009, at the Moody Music Building on the UA campus. There will be a visitation from 8:30-10 a.m. and the service will follow at 10 a.m. Bank will be buried alongside his parents, Sam and Bessie Bank, and his brother, Harold, at Evergreen Cemetery. Graveside services, with full military celebrations, will be held at 11 a.m. Born on 1 September 1914 in Montgomery, Alabama, he was 94.

I won't be there, as I have been ordered by my doctor to stay off my right foot if I want to continue having it attached to my right leg. I wish I could be.

The service will be slightly over 67 years late, for that is how long Bert beat the terrible odds he was faced with early in life. But, oh, what he did with that life.

Bertram Bank was born in 1914 to Russian Jewish parents who had emigrated to the United States from a village near the Polish border. he grew up on the coalfields of Tuscaloosa County near the small mining town of Searles. The Great Depression had all but decimated his father's restaurant and plumbing businesses, but Bert somehow saved up enough money to realize his dream of a college education and enrolled at the University of Alabama. The affable extrovert spent four cherished years at the Capstone, working at the school paper, drilling with the R.O.T.C. detachment, and making friends, one of whom was a rugged, lanky football player named Paul Bryant. He intended to pursue a career in law, but with the winds of war sweeping the nation, Bert soon found himself flying dive-bombers instead of filing legal briefs.

Assigned to the 27th Bombardment Group at Hunter Field in Savannah, Georgia, lieutenant Bank trained in the skies by day and entertained his share of Georgia belles-including the winner of the 1939 Miss Georgia pageant-by night. On November 20, 1941, Bert and his comrades arrived at Fort McKinley in the Philippines. -- John D. Lukacs, When Men Must Die: An Alabama POW at Bataan, Alabama Heritage, Fall 2003.

After Bert's squadron's planes were destroyed on the ground thanks to the dithering MacArthur's hesitation, Bank and his friend Bill Dyess ended up fighting, and starving, as infantrymen on Bataan.

"On Christmas Eve, General Douglas MacArthur moved everybody to the Bataan Peninsula," said Bert. "All air force personnel became infantry. They put all of us on the front lines. We were fighting as infantry with no training."

And yet they fought well. With the fall of Bataan, Bank and Dyess fell in together at the surrender and Dyess later recalled their initiation into Japanese military ethics.

Death March survivor and friend of Bert Bank, LTC William Dyess.

Death March survivor and friend of Bert Bank, LTC William Dyess."The victim, an Air Force captain, was being searched by a three-star private. Standing by was a Jap commissioned officer, hand on sword hilt. These men were nothing like the toothy, bespectacled runts whose photographs are familiar to most newspaper readers. They were cruel of face, stalwart, and tall.

'The private, a little squirt, was going through the captain's pockets. All at once he stopped and sucked in his breath with a hissing sound. He had found some Jap yen.'

'He held these out, ducking his head and sucking in his breath to attract notice. The big Jap looked at the money. Without a word he grabbed the captain by the shoulder and shoved him down to his knees. He pulled the sword out of the scabbard and raised it high over his head, holding it with both hands. The private skipped to one side.'

'Before we could grasp what was happening, the black-faced giant had swung his sword. I remember how the sun flashed on it. There was a swish and a kind of chopping thud, like a cleaver going through beef'.

'The captain's head seemed to jump off his 'shoulders. It hit the ground in front of him and went rolling crazily from side to side between the lines of prisoners.'

'The body fell forward. I have seen wounds, but never such a gush of. blood as this. The heart continued to pump for a few seconds and at each beat there was another great spurt of blood. The white dust around our feet was turned into crimson mud. I saw the hands were opening and closing spasmodically. Then I looked away.'

'When I looked again the big Jap had put up his sword and was strolling off. The runt who had found the yen was putting them into his pocket. He helped himself to the captain's possessions.'

This was the first murder. . ." -- William E.Dyess, The Dyess Story, 1943.

Then began the Death March.

The Bataan Death March-depending on where and when a prisoner joined the slow, suffering column-was actually a series of forced marches lasting from five to ten days, covering approximately sixty-five miles from Mariveles to the rail hub of San Fernando, in the northern province of Pampanga. Bert weaved through the smoldering jungle, passing abandoned, fire-gutted, olive-drab vehicles licked by dying flames and centuries-old banyan trees splintered by shrapnel and shell. Through the choking dust clouds kicked up by the ghost-like, khaki silhouettes plodding in front of him, he spotted artesian wells bubbling with cold, clear spring water, but he dared not stop. Bert quickly learned that the Japanese summarily executed anyone who strayed from the march. Each evening, the drained, disease-wracked prisoners would collapse in a vacant schoolyard or sugarcane field. Lucky prisoners received a single ball of rice, about the size of a baseball, to eat. Most received nothing.

At first light, cracks of rifle fire echoed throughout the rolling green hills. Some guards pumped bullets into those physically unable to keep the grueling pace; others delivered death with samurai swords. As the blistering midday sun slowly arced across the powder-blue tropic skies, temperatures soared to stifling, triple-digit figures. Prisoners watched helplessly as guards gunned down weak comrades who stopped to rest without permission or others who made the fatal mistake of possessing anything stamped "Made in Nippon"-the logic of the guards being that one had to have taken the object from a dead Japanese soldier. Even the desperate, thirst-crazed men who lunged for roadside carabao wallows-shallow pools of filthy, brackish water in which floated bullet-riddled corpses and the rotting carcasses of dead horses-received swift, fatal reprimands from Japanese bayonets. Inflated with rage, yet weak, unarmed, and powerless to interfere, they could only watch the slaughter in utter disbelief. For four months, they had seen comrades killed honorably by bombs and shells and bullets in combat. But they had not been prepared for this. Questions abounded in Bert's mind, and answers were not forthcoming.

"The thing in my mind when we started the Bataan Death March was, what happened? America's abandoning us," says Bert. "We didn't understand this." -- Lukacs, Ibid.

Banks later wrote:

On this march I was with my very good friend Lieutenant Colonel Dyess who escaped in 1943 and successfully reached the States and gave the American people the first information concerning our prison life and the March of Death. The third day of this march, Dyess amd I were very thirsty and we stepped to the right a few feet and attempted to get a drink from an artesian well. A guard shot at me and missed, but killed a Filipino standing right next to me. This was not an unusual incident, as many of us were desperate for water. For the entire five days the Japs gave us no water at all. After seeing so many killed on the attempt, few of us would dare try to get the water. On this march we were given one small rice ball about the size of a fifty cent piece. Our lips were so blistered and raw that we could not eat even this small amount of rice. That is all the food the Japs gave us during these five days and nights of horror. . . The third night it rained very hard and about midnight the Japs said we could rest . . . During this second of rest, I fortunately sat down in a mud hole and I drank the water from this hole, even though animals and humans had marched through it for days.

Along the highway one saw bodies maimed and completely decapitated as the result of the Jap trucks along the highway. The Japs in these trucks would hit the Americans on the head in passing. One day a Jap in a passing truck attempted to decapitate me and I ducked and he completely cut off the head of a Filipino standing next to me. One day during the march we heard a blood-curdling scream and when we looked over into a nearby rice pattie we saw a guard cutting the stomach out of a poor old Filipino. I was later told that the Filipino had refused to march any farther. The Filipino was not dead when they finished cutting out his stomach and he was begging the guard to shooy him, but he was refused even that. One person told me that he, along with other Americans, had been required to eat pieces of human flesh during the march . . . -- Back From the Living Dead, Major Bert Bank, 1945.

Yet for all that, other POWs recalled that it was Bert who kept them going with his irrepressible sense of humor.

After five days on the march, Bert staggered into San Fernando, where he and more than a hundred other prisoners were prodded into a musty World War I-era steel boxcar-designed to hold only forty-for a tortuous, twenty-four-mile journey. Many prisoners, suffocating under the oppressive heat, fainted. Those suffering from dysentery soiled their threadbare uniforms. Others died standing upright, unable to slump to the floor. When the train finally screeched into Gapas, in Tarlac Province, dozens fell out onto the station platform gasping for fresh air. Six miles later, Bank found himself standing before the gates of Camp O'Donnell, the first of three squalid Japanese prison camps that he would call home for the next three-and-a-half years. Unlike nearly seven hundred of his countrymen and ten thousand of his Filipino allies, he had survived the Bataan Death March. But his ordeal was only just beginning.-- Lukacs, Ibid.

For almost three years, Bert Bank suffered at the hands of the Japanese, from Camp O'Donnell, to Cabanatuan, then to a former leper colony in Davao and finally back to Cabanatuan. It was there that Bert Bank was rescued by the Rangers, as portrayed in the movie The Great Raid.

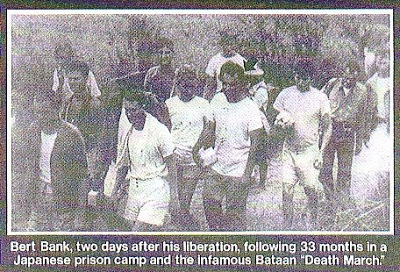

Picture of Bert and rescued comrades from his memoir, Back From The Living Dead.

Picture of Bert and rescued comrades from his memoir, Back From The Living Dead."The liberation by the Rangers was a great, great thing," says Bert. "If they hadn't been successful, the Japanese would definitely have eliminated us."

The resurrected "ghosts" were treated to an unlimited menu from the 12th Battalion Replacement Center field kitchen, given much-needed medical attention, and greeted by General MacArthur himself. According to Bert, a visibly emotional MacArthur shook hands with the former prisoners and personally welcomed each man back. "One guy said to him, 'How come it took you so long?'" said Bert. . . Bert spent the early part of 1945 convalescing overseas and steadily regained his sight. he returned home to Tuscaloosa and, after checking out of Northington General Hospital with a clean bill of health, was promoted to the rank of major. Bert spent the remainder of the war a celebrity, traveling the country selling war bonds for the Treasury Department. . . -- Lukacs, Ibid.

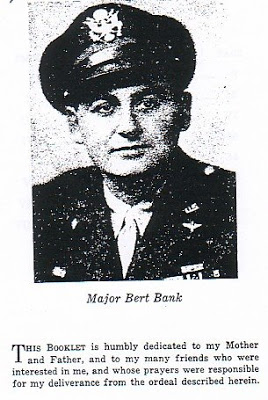

Upon his return, Bert wrote his memoir, a small pamplet of a book of 108 pages with black cover and stark white letters: "Back From The Living Dead: The infamous death march and 33 months in a Japanese prison." In it, he included this postwar photo and dedication:

Bert left the service in 1946. Despite suffering from recurring nightmares like many former prisoners, he made a highly successful transition to peacetime life. he became a radio entrepreneur, eventually owning several Tuscaloosa stations, which, at the request of his old friend Bear Bryant, he used to help create the Crimson Tide football radio network. he entered politics in 1966 and was elected to three terms, two in the Alabama House of Representatives and one in the Senate and served as floor leader in the administrations of three governors-George Wallace, Lurleen Wallace, and Albert Brewer. he also ran for lieutenant governor in 1978, but lost in a tight race. Between his political and business careers, Bert found time to raise two sons-Ralph and Jimmy-with his late wife of thirty-four years, Gertrude. -- Lukacs, Ibid.

Alabama Gov. George C. Wallace's "stand" in the schoolhouse door at the University of Alabama on June 11, 1963. This is a photo of Wallace entering a motel in Tuscaloosa. Surrounding cast includes (1) Wallace; (2) Lonnie Falk, then a student at UA; (3) UPI's Gary Haynes of UPI-Atlanta and assorted other bureaus, later Times and Inquirer editor; (4) Rex Thomas of AP-MG; (5) Gerald Wallace, the governor's brother; (6) Ralph Roton, Klan member, official and head of self-styled Klan Bureau of Investigation. Also standing behind state trooper on the far left is Tuscaloosa businessman Bert Bank, a survivor of the Bataan Death March who was later elected to the Alabama Senate.

Alabama Gov. George C. Wallace's "stand" in the schoolhouse door at the University of Alabama on June 11, 1963. This is a photo of Wallace entering a motel in Tuscaloosa. Surrounding cast includes (1) Wallace; (2) Lonnie Falk, then a student at UA; (3) UPI's Gary Haynes of UPI-Atlanta and assorted other bureaus, later Times and Inquirer editor; (4) Rex Thomas of AP-MG; (5) Gerald Wallace, the governor's brother; (6) Ralph Roton, Klan member, official and head of self-styled Klan Bureau of Investigation. Also standing behind state trooper on the far left is Tuscaloosa businessman Bert Bank, a survivor of the Bataan Death March who was later elected to the Alabama Senate.No man is perfect. Neither was Bert Banks. He opposed the desegregation of the University of Alabama, not on racial grounds (the Klan hated him for being both Jewish and a "nigger lover") but rather on states rights objections. His support of Wallace drew him into Alabama politics, but he never believed in the racial theories of the Klan. As sportscaster Paul Finebaum recalled:

While his memories from the Pacific are well known and documented, there are many other things about Bank rarely discussed. For instance, he was the first white radio-station owner in Alabama to put a black DJ on the air in the late '50s. "A bunch of advertisers threatened to cancel, and I told them I would publish their names in the paper if they did," Bank said. Most backed down. Bank, who owned two stations in Tuscaloosa, gave many students their first job at WTBC-AM, including a number who have gone on to major network jobs.

If Bert Bank needs an epitaph beyond his amazing life, do not use the word "hero" in it. Bert always denied he was a hero, saying the real heroes were the soldiers who never came home. And as John Lukacs wote:

Bert retired in 1985, but he still maintains an office at WTBC as "producer emeritus" and attends every Alabama football game, home and away (he's missed just three games in the past forty-eight years), with the station broadcast team. After the death of his wife, he was reunited with Emma Minkowitz Friedman, the former Miss Georgia he had met more than sixty years earlier in Savannah, and remarried in 1997.

Almost six decades later, Bert has not forgotten his country. he tells his story regularly at schools and at meetings of Kiwanis and Rotary clubs across the state. He's been the guest speaker at dozens of Memorial and Veterans Day events for years. He's even given pep talks to Crimson Tide athletic teams. In short, he'll sound the praises of his country anywhere and for any audience who will listen. That's because Bert Bank, once forgotten himself, will never forget the night his country came back for him.

4 comments:

An absolutely amazing story.

Maybe I need to read more about the march, but I never understood how someone could stand by and wait to be slaughtered. Knowing that they will only become weaker as time goes on from a lack of food and water and rest. I would think the urge would be to lash out.

I guess I wouldn't last long as a prisoner, I'd be killed quickly, hopefully not without taking some of those frak'ers with me!

This is the dilemma "US III" now find ourselves in by my estimation.

Excellent piece of history! Thanks!

The survivors of Bataan and Correigidor (sp?) never knew how much their brave stand effected the war. By holding out as long as they did, they threw the entire Japanese timetable off and made it possible for America to mobilize our forces.

Every one of these men is a hero.

Mike thanks for this piece, and all the others you have shared with us.

These guys gave the full measure to their country, how can we do any less?

Dr.D

Post a Comment