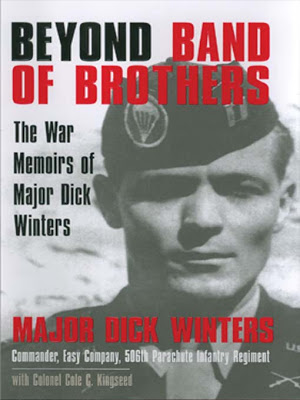

I picked up Beyond Band of Brothers: The War Memoirs of Major Dick Winters at Books-A-Million the other day for the modest price of $3.97. It is a great read. Here are some excerpts on leadership:

An officer should never put himself in a position where he takes anything from the men. Never abuse them by act or omission. As a commander a leader must be prepared to give everything, including himself, to the people he leads. You give your time and you strive to be consistently fair, never demonstrating favoritism. . . (pp. 61-62)

With the invasion now only weeks away, I refocused my efforts for the task at hand. Whether or not I wanted to admit it, the past few months had been a battle of nerves and nobody was any worse for wear than I. I found refuge in church, having only missed services three times in over eight months. . . I was happy to be an officer, but I wrote one friend back home that it was not all that it was cracked up to be. . . Despite the fact that I had been an executive officer for fifteen months, and that I was the only officer left in the company who had started with the unit at Toccoa, I still wore the rank of a 1st Lieutenant. But that was okay because I knew my job, my company, the men, and I felt confident that under fire, I had the right answers. Which gets me to the point: I was a "half-breed." An officer yes, but at heart an enlisted man. I worked hard and did my duty as I should, but when it came to play, I was in a bad position and only in athletics with the men did I enjoy myself. . .

With the reflection of sixty years, I can say that I was not too concerned about the invasion. I truthfully never wavered as to whether or not I would succeed in combat. I was far more concerned for the safety of the men entrusted to my command. Any success I had as a battlefield commander was based on character, detailed study, and taking care of thos troopers. In one letter I painted a beautiful, pathetic, and touching portrait of what leadership consists of. Picture if you will, a small unit exercise in the English countryside on the eve of the invasion. Along a roadside on a cold damp morning sits a private with his machine gun. He has been on the march amd fighting for just about twenty-four hours without stopping or sleeping. He is tired, dead tired, so tired his mind is almost a blank. He is wet, hungry, and miserable. As his buddies sleep, he keeps watch, a difficult job when he is so exhausted and he knows that when the sun comes up in another half hour, he will once again be on th move. What does he do? He pulls out a snapshot of his girl, who is over 3,000 miles away. amd studies her picture. In a state of inner tranquillity, he dreams of days when he can once again enjoy the kind of life she stands for. Down the road comes an officer -- it's me. Nobody else would think of being up at a pre-dawn hour. "How's it going, Shep? What are you doing?" Then together, we study and discuss his girl's good features and virtues. He asks me to promise that I will ensure he survives the upcoming battle -- a promise I cannot make in good faith since I don't know what the final outcome of the battle will be. I can only tell Shep that I will do my best to ensure he comes home safely -- a promise that I kept.

When you think about kids like that, and you realize the weight of your responsibility and do something about it, you soon become old beyond your years. In three years, I had aged a great deal. Still only twenty-six years old, I felt that the simpler times of my college experience and the days of civilian life when I did as I pleased, were long past. It must have been a dream, a small, short but beautiful part of my life. Now all I did was work -- work to improve myself as an officer, work to improve my soldiers as fighters, and work to develop them as men. The result was that I was old before my time; not old physically, but hardened to the point where I could make the rest of them look like undeveloped high school boys; old to the extent where I couod keep going after my men fell over and slept from exhaustion, and I could keep going as a mother who works on after her sick and exhausted child has fallen asleep; old to the extent where if it was a decision or advice needed, my decisions were taken as if the wisdom behind them was infallible. Yes, I felt old and tired from training these men to the point where they were now efficient fighters. I hoped that the effort would mean that more of them would return to those girls in the States than otherwise would have made it back to the comfort of their families and friends. . . (pp. 64-66)

Day of Days

At long last, D-Day was over. Our success had been due to superb leadership at all levels and the training we had experienced prior to the invasion. Add luck to the equation, and Easy Company comprised a formidable team. On reflection, we were highly charged; we knew what to do; and we conducted ourselves as part of a well-oiled machine. Because we were so intimate with each other, I knew the strengths of each of my troopers. It was not accidental that I had selected my best men, Compton, Guarnere, and Malarkey in one group, Lipton and Ranney in the other. These men comprised Easy Company's "killers," soldiers who instinctively understood the intracacies of battle. In both training and combat, a leader senses who his killers are. I merely put them in a position where I could utilize their talents most effectively. Many other soldiers thought they were killers and wanted to prove it. In reality, however, your killers are few and far between. Nor is it always possible to determine who your killers are by the results of a single engagement. In combat, a commander hopes that nonkillers will earn by their association with those soldiers who instinctively wage war without restraint and without regard to their personal safety. The problem, of course, lies in the fact that casualties are highest among your killers, hence the need to return them to the front as soon as possible in the hope that other "killers" emerge. This core of warriors survived, at least until the fates abandoned them, because they developed animal-like instincts of self-preservation. Around this group of battle-hardened veterans the remainder of Easy Company coalesced. Other leaders emerged as the war progressed, but the best leaders were those who had endured combat on D-Day and matured as leaders as they gained additional experience.

As for myself, I never considered myself a killer although I had killed several of the enemy. Killing did not make me happy, but in this particular circumstance, it left me momentarily satisfied -- satisfied because it led to confidence in getting a difficult job done with minimal casualties. Nor did I ever develop a particular hatred for the individual German soldier. I merely wanted to eliminate them. There is nothing personal about combat. As the war progressed, I actually developed a healthy respect for the better units we faced on the battlefield. But that was all in the future. For the time being, I was just happy to have survived my baptism by fire. I had always been confident in my own abilities, but the success at Brecourt increased my confidence in my leadership, as well as my ability to pass it on to my soldiers. (pp. 93-94)

3 comments:

Damn fine insights from a damn fine man. We may have good men, but we never had better.

May we have leaders like that when we need them most.

Currahe!

Indeed worthy to be "father" to a band of brothers. A true philosophical descendant of Henry V, leading from among, not behind.

Post a Comment