“Don’t

resist – you’ll just make it worse.”

Until

recently, the only people expected to make that demand of their innocent victims

were rapists and police officers. Fortunately, women are no longer expected to

submit to sexual assault, but rather to fight back by whatever means are available

– unless the assailant is one of the State’s costumed enforcers, in which case

resisting sexual assault would be a felony.

This

admission was pried from Gregory J. Babbitt, assistant prosecuting attorney for

Michigan’s Ottawa County, during the October 4 oral

argument before the state supreme court in the case of People v. Moreno. At issue in that case is the question of whether a citizen

has a legally protected right to resist an unlawful search or unjustified

arrest by a police officer.

In

a colloquy with Babbitt, associate justice Michael

Cavanaugh described a scenario in which a woman in police custody

was sexually assaulted during a body search. In that situation, Cavanaugh

inquired, could the victim be charged under the State’s “resisting and

obstructing” statute?

“Technically,

you could do that,” Babbitt grudgingly replied, while insisting that “as a

prosecutor, I wouldn’t do that.” Rather than putting up physical resistance and

thereby risking criminal prosecution, the victim should simply endure the assault

and then file a civil complaint after the fact. That approach, of course, would most likely result in a

settlement that protects the offender at the expense of the local tax victim

population.

If

citizens have no right to resist illegal violations of their property and

persons by the police, “What is left of the Fourth Amendment?” one of the

judges asked Babbitt.

“Well,

life isn’t perfect,” Babbitt replied with a shrug – which to people of his ilk

means that in any conflict between individual liberty and institutionalized

power, it is the former that must yield. Otherwise, mere Mundanes “will be able

to make the determination as to whether the police officers [are] acting

properly or not,” he said, his voice freighted with horror over the prospect. “We

can’t have individuals ... making that decision in the heat of the moment.”

Of

course, that is precisely what Babbitt insisted must be done – as long as the “individuals”

in question are emissaries of the State. That claim is

complicated by the fact that Michigan’s self-defense act explicitly recognizes

the right to use appropriate defensive force to prevent the “imminent unlawful

use of force by another individual” – without limiting the application of that

right to aggression committed by private citizens.

Furthermore,

as the Michigan Court of Appeals recognized in a 1999 ruling (People v. Wess), the statute -- as it read at

the time -- expressly recognized the individual right "to use such reasonable

force as is necessary to prevent an illegal attachment and to resist an illegal

arrest."

In the dicta of that ruling the court pleaded with the

legislature to change the law:

"We

share the concerns of other jurisdictions that the right to resist an illegal

arrest is an outmoded and dangerous doctrine, and we urge our Supreme Court to

reconsider this doctrine at the first available opportunity.... [W]e see no

benefit to continuing the right to resist an otherwise peaceful arrest made by

a law enforcement officer, merely because the arrestee believes the arrest is

illegal. Given modern procedural safeguards for criminal defendants, the

`right' only preserves the possibility that harm will come to the arresting

officer or the defendant."

Of

course, there is no such thing as a “peaceable arrest.” Forcible detention is a

violent act, as is an armed invasion of one’s property. Like similar measures

protecting the common law right to resist arrest, Michigan’s SDA recognized there

is no moral reason why a police officer’s judgment that a search or arrest is “legal”

is any sounder or more authoritative than that of any other citizen.

However,

the Michigan state legislature – prompted by the

Court of Appeals -- modified the relevant section of the state code (MCL

705.81d) by removing the clause recognizing the common law right to prevent an

unlawful arrest (that is, an armed kidnapping) by a police officer.

This

created a potential conflict between the SDA and the state’s resisting and

obstructing statute – and that conflict came to a head three

years ago when two Holland, Michigan police officers attempted to search

the home of Angel Moreno without a warrant.

On

December 30, 2008, Officers Matthew Hamberg and Troy DeWeis knocked on Moreno’s

door while searching for an individual suspected of violating probation. Moreno

made the mistake of speaking with Hamberg through an open door, thereby giving the policeman an opportunity to say that he detected the odor of marijuana (even though DeWeis did not).

When

Moreno refused to consent to a search, Hamberg said that he would get a warrant

– and then lied by saying that it was necessary for him to enter the house in

order to “secure” it.

To his credit, Moreno told Hamberg to get off his porch,

and began to close the door. Hamberg bulled his way into the house, instigating

a brief scuffle that ended when Hamberg told his companion

to attack the victim with his Taser. (Had DeWeis acted as the law requires, rather than out of tribal loyalty to his State-licensed gang, he would have intervened to prevent the invasion of Moreno's home.) Although a trivial amount of marijuana was

found, no drug-related charges were filed. For trying to resist a patently illegal

home invasion, Moreno charged with felonious assault on a police officer.

The

State admits that Hamberg’s search was “unlawful,” which means that he was acting

as an armed, violent intruder, rather than as a peace officer. This means that

Moreno had a legally recognized right to employ deadly force, if necessary, to

defend himself and his home. As the Michigan State Supreme Court acknowledged

in People v. Riddle (2002), “regardless

of the circumstances one who is attacked in his dwelling is never required to

retreat where it is otherwise necessary to exercise deadly force in

self-defense. When a person is in his `castle,’ there is no safer place to

retreat….”

Michigan

courts have been predictably reluctant to apply that principle to the most

violent segment of society – the State’s armed enforcement caste.

In

a 2004 ruling (People v. Ventura) dealing with the right to

resist an unlawful arrest, the same Michigan Court of Appeals, which had badgered

the state legislature to modify the SDA, cited that modification as a positive

statement of legislative intent. In a transcendently cynical passage, the court

wrote that "it is not within our province to disturb our Legislature's

obvious affirmative choice to modify the traditional common-law rule that a

person may resist an unlawful arrest."

The same court had previously neglected to show such pious respect for the "Legislature's obvious affirmative choice" in explicitly protecting the right to resist arrest. However, under state precedents more than a century old, the Michigan legislature cannot tacitly repudiate a common law right. As Justice Brian K. Zahra noted during the oral arguments, the legislature is required to make an "express abrogation" of protection for a common law right.

During

his presentation before the court, Babbitt -- in the mistaken belief that he had precedent on his side -- repeatedly insisted

that deletion of the passage recognizing the right to resist arrest was materially equivalent to formal abrogation of that common law right. This was dictated by the “modern

view" of the matter, which is that “we don’t want violence between the citizens and the

police.”

Indeed:

The modern – which is to say, Leninist – view is that all violent encounters

between citizens and agents of the State should be one-sided affairs, with the

latter entitled to exercise “power without limit, resting directly on force”

and the latter required to endure whatever is inflicted on them.

Remarkably,

Babbitt’s argument was met with withering skepticism by several members of the

court. Among them was Chief

Justice Robert P. Young, Jr., who asked Babbitt what “textual” support

existed for the proposition that the legislature had abrogated the common law

right to resist arrest.

“I

can’t answer that question, because it doesn’t say `We are abrogating the common

law right to use self-defense,'” Babbitt replied, perspiration condensing on his

brow as he realized where the conversation was headed.

“I

think you answered it, then,” Young replied, thereby -- one imagines -- causing that trickle of

flop sweat to become a torrent. “Don’t you lose if you can’t answer that

question?”

Babbitt was allowed a brief

interval in which to dither and dissimulate before Young summarized the matter

with brutal concision:

“I’m

posing a very simple question to you, the answer to which, I think, is

dispositive: If the arrest is unlawful, if the intrusion is unlawful, and a

physical melee ensues because of the resistance of the resident, under the

common law rule, he can do that…. You don’t win [the case] unless you can

persuade us that the [statute under which] he was charged abrogates the common

law rule. Tell me why, when the text is silent on the common law rule, you

still win.”

At

that point, Babbitt must have understood – but could hardly be expected to

admit – that as a matter of both common and statutory law, the “rapist doctrine”

is indefensible.

It’s quite possible, perhaps even likely, that the state

supreme court will contrive some way to preserve that doctrine. If the court’s

ruling in State v. Moreno vindicates

the right of citizens to resist unlawful police violence, the state legislature

will be tag-teamed by prosecutors and police unions demanding an explicit

repudiation of that common law right.

But

what if the Michigan State Supreme Court definitively rejects the "rapist doctrine" -- and the state legislature does

likewise?

A special request

First of all, I want to thank everyone who has donated generously to keep this site up and running. If there is anyone who has yet to receive a promised copy of Global Gun Grab, please let me know (WNGrigg [at] msn [dot]com).

When friends ask me if I'm working, I -- like may others, I'll wager -- answer: "Sure, I've got the `working' thing nailed cold, it's the `getting paid' part of the deal that has proven elusive."

Over the past couple of months I've been working with Republic

magazine (please check out the website), a very worthwhile publication

that, to be candid, doesn't pay well -- enough to pay the rent, but not

enough to support a family of eight.

Christmas is terrifyingly close, but the end of our available financial resources is even closer. If even a portion of those of you kind enough to read my blog could pitch in a couple of dollars, I would be eternally grateful. Thank you, once again, for your kindness.

Dum spiro, pugno!

13 comments:

no need to post

Greetings Will,

Shared

Thank you for writing this essay

Doc Ellis 124

no need to post

How exactly is the right to resist illegal arrest "dangerous and outmoded"? It is not at all safe to allow someone who wants to illegally detain you to do so. What great advance in ensuring bodily integrity and safety has made self-defence "outmoded"?

Or did they mean that this doctrine was dangerous to those who would illegallly arrest people. I did not know that the law took any notice of how dangerous crime was for the criminal.

Or did they mean that this doctrine was dangerous to those who would illegallly arrest people[?]

Yes, that's exactly what they mean. Anything that challenges the implied supremacy of the State over the individual is, in the minds of the Ruling Classes, inherently "dangerous."

It's all about the State wanting to corral the public into their sheep pens. YOU, citizen/slave, are not to question nor resist their supremacy. To do so would, in our present day Leninist overlords' minds, constitute an "existential threat". The laws being rammed through Congress are to pave the way to justify past, present and forthcoming abuse by goose-stepping LEO's and their more than happy to enable legal beagles.

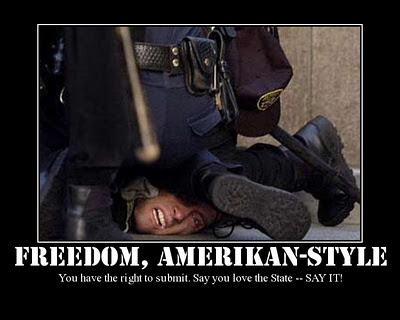

That photo of the woman at the top of the page – I remember that and used to have larger photos showing it at different angles; the cops completely destroyed her knee, and her foot seemed close to her face, yet look at the cops – one of them has her by the wrist as if he is going to handcuff her. And the other cops are keeping people away from her; “crowd control,” I guess. I was enraged when I saw that.

Of course, she had to be carried away from there in an ambulance and, if I recall, she had to have several surgeries on her knee. I’m pretty sure it wasn’t the cops who summoned medical help; they seemed not to notice that her leg was bent forward in such a sickening, abnormal way. I saw another picture of her in a courtroom, in a wheelchair, with her heavily bandaged leg propped outward. Whether her knee was ever the same, I don’t know. Do you know her name? I’d like to look it up. THOSE ANIMALS – could they not make one exception to the rule of handcuffing her and pretending that she was somehow fighting back and call for an ambulance? She was obviously seriously injured, perhaps unconscious from the pain. BUT NO. They have a script from which they never waver – grab the wrists, FLAY THE WRISTS AROUND THEMSELVES, as though the person is doing it, as “proof” that the person is fighting, or “resisting.”

I’ve shown these photos to several people and the reaction I get is NOTHING. Maybe they think “she must have done something to deserve it.”

I believe I’ve mentioned this before, but I saw a video of a man in prison, an old black man that the cops were beating and tasing and shouting “Stop resisting!” At the end a cop yelled “Stop re–...” He couldn’t finish the command, because the man was already dead and had been dead for awhile.

The topmost photo is indeed disgusting. If you haven't already noticed the goon with his arm out looks to be holding something like mace. And they have the prototypical buzz cuts. I swear! If there isn't a clearer sign of fleas on these mad dogs.

I opened up my Black's Law Dictionary, and the definition of "arrest" begins with the following:

"To deprive a person of his liberty by legal authority."

An "unlawful arrest" is a contradiction in terms! It's an incoherent concept!

@ William JD -- What you're referring to is best described as an abduction, rather than an arrest. I've typically referred to the "right to resist unlawful arrest," which, as you point out, incorporates an oxymoron. It would be more accurate to refer to the right to resist official abduction, perhaps.

Mr. Grigg

A "contradiction in terms" is not synonymous with "oxymoron." An oxymoron is, in fact, a seeming contradiction that is surprisingly true.

I am tired of this belief that most Americans have that police are gods. And because they are gods they can do anything and everything they want. The truth is the police are hardly gods, and they are just as likely, if not much more likely, to commit crimes than anyone else.

What's the big problemo with unlawful search?? I don't get it. They ARE the police and can lie, beat, and hammer their way to justice. My God..where's Himmler when you need him? He had the answers to all these whining complaints.

Unfortunately in New York State the 'law' specifically does not allow resistance of any arrest. I quote

S 35.27 Justification; use of physical force in resisting arrest prohibied.

A person may not use physical force to resist an arrest, whether

authorized or unauthorized, which is being effected or attempted by a

police officer or peace officer when it would reasonably appear that the

latter is a police officer or peace officer.

This really sucks because NYC has the worlds most militarized over the top out of control SS.

I was unaware that the state could simply make a new law to overturn a right recognized by the USSC in Bad Elk.

Post a Comment