Shortly before dawn on April 30, Steve Nelson was robbed and fatally beaten by three assailants at near Lake Lowell in Canyon County, Idaho. Nelson had contacted Kelly Bryan Schnieder, who has admitted his role in the attack, through the “male escort” section of the “Backpage” social media site.

After they met at Gotts

Point trail head, Nelson offered to pay

Schneider for sex – not knowing that he was about to fall prey to a “trick-rolling”

gang led by a charming specimen named Jayson Woods. An equal opportunity predator, Woods

later admitted to police that “he sets people up for sexual acts, then

takes all the money that is `donated’ to them, then divides the money at the

end of the night.”

On some evenings Woods had conscripted an

unwilling ex-girlfriend to act as the lure. For the gig at Gotts Point, he

enlisted Schneider, a

convicted burglar who was on probation at the time of the April 30

incident.

Shortly after Schneider made contact with

Nelson, he was joined by two others – Daniel

Henkel and Kevin Tracy – who helped restrain the victim while Schneider

repeatedly slugged him in the face and kicked him with steel-toed boots. Pleading

for his life, Nelson surrendered his debit card and gave the assailants his PIN

number. After stripping Nelson, they drove off to the nearest ATM, where they

vacuumed out his checking account, which gave them a total of $123 to apportion

among themselves.

Naked and bleeding, Nelson staggered to a

nearby home, knocked on the door, and asked the owner to call 911. He was able

to identify Schneider before dying of cardiac arrest a few hours later.

Nelson had been an employee at Boise State

University and a gay rights activist. Adriane

Bang, director of BSU’s Gender Equity Center, insists that the hideous

crime committed against him underscores what

she describes as “the reality that our community can be a hostile and

sometimes very dangerous place for folks who identify as LBGTQIA.”

It’s important to recognize that Nelson

wasn’t randomly attacked in a public street in broad daylight, or victimized in

the security of his own home. He placed himself in danger by soliciting sex

from a stranger in exchange for money in an isolated location. Activities of

this kind shouldn’t be criminalized, but they do involve an assumption of risk.

Ms. Bang also compared the killing at Gotts

Point to the 1998 murder of Matthew Shepard in Laramie, Wyoming, a parallel

that may be apt in ways she most likely had not intended.

Slight of build and entirely helpless,

Shepard was robbed and beaten by two opportunistic criminals he had met in a

bar. After being fatally pistol-whipped, the mortally wounded victim was tied

to a fencepost.

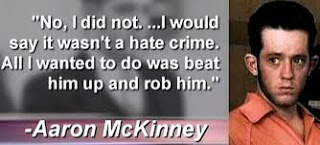

Shepard was immediately beatified as a “gay

martyr” and his name was immortalized in a federal hate-crimes bill. High

school students across the nation are catechized in the canonized version of

the Matthew Shepard martyrdom by a traveling agit-prop theater troupe called “The

Laramie Project” – despite the fact that the crime committed against him had

nothing to do with his sexual self-definition.

“The murder was so vicious, the aftermath

so sensational, that the story first told to explain it became gospel before

anyone could measure it against reality,” observes

JoAnn Wypijewski, one of the few journalists

who spent time in Laramie trying to winnow the truth from the sensationalistic

chaff. “For different purposes, two sets of friends created what became the

hate crime story. Without knowing the circumstances of the crime, Shepard’s

friends told reporters, officials and gay groups that the victim’s sexuality

was all one needed to know. Meanwhile, [murderer Aaron McKinney’s] friends told

police various versions of a gay panic story, in which Matthew made advances

and Aaron snapped.”

Police investigators and the District

Attorney added their own embellishments by claiming, without evidence, that

McKinney and his accomplice Russell Henderson “had pretended they were gay to

lure Shepard out of the Fireside bar and into a fatal trap.”

As gay rights activist turned-investigative

author Stephen

Jimenez documents in his deeply reported volume The

Book of Matt, Shepard was the fourth victim who was beaten by McKinney on

the day of the murder. None of those crimes had anything to do with the sexual

identity of the victims. All of them – including the killing of Matthew Shepard

– were related to McKinney’s drug addiction, a fact grudgingly conceded by

prosecutor Cal Rerucha in

an interview with ABC’s 20/20 program.

McKinney

himself would probably be characterized today as “gender-fluid.”

The owner of a gay bar in Denver recognized him as a regular patron. Several

acquaintances of Shepard who had no reason to lie or denigrate his memory told

Jimenez that the victim and his eventual killer had been involved in consensual

carnal relations prior to the murder. Shepard himself, Jimenez discovered after

years of careful research, was

both a meth dealer and an addicted user who had dabbled in heroin, and was

HIV-positive at the time he was killed.

Despite his instant and politically

convenient beatification, Shepard was not a casualty of an anti-gay “hate

crime.” To the extent that public policy played a role in his death the fault

was not a lack of punitive strictures for “anti-gay” attitudes, but rather the

State’s insistence on criminalizing narcotics use, thereby diverting it into

the violent demimonde in which murders of this kind are relatively common.

The only reason for treating the murder of

Matthew Shepard as a “hate crime” was the identity of the victim. This is

likewise true of the murder of Steven Nelson.

In an

op-ed column for the Idaho Statesman,

Jordan Brady, a spokes-something-or-the other (I’ve not received adequate guidance

regarding the

officially mandated pronoun) for a vaporware- grade

special interest group calling itself Better Idaho, characterized the

robbery-murder of Nelson as an act of “domestic terrorism” that must

be treated as a federal hate crime.

“On April 29, Nelson was targeted because

he was gay,” contends Brady. This is entirely untrue: He made himself a target by seeking a covert assignation with a

stranger who proved to be part of a vicious knot of deranged criminals.

“Unfortunately,” Brady complains, “the

suspects in the case are immune from Idaho’s hate crime laws, which currently

only protect victims on the basis of race, color, religion, ancestry, or

national origin.”

This supposed immunity did not prevent the identification,

arrest, and arraignment of the suspects on first-degree

murder charges that could result in live imprisonment without the

possibility of parole. Laws against murder did not “protect” Nelson from being

fatally beaten by criminally minded people who assumed they would elude punishment.

Adding another “specially protected class” to the spurious hate crimes law

would not have changed either of those outcomes. But this consideration doesn’t

matter to collectivists who do not see the purpose of law as protecting

individual persons and private property.

Hate crimes laws are important, Brady

asserts, because “the victims of hate crimes are entire communities, not just

individuals. With the murder of Steven Nelson, it was the LGBTQ community….

[Hate crimes are] acts of terrorism against a community.”

I pause to note that Brady apparently

dropped a few letters from the most recent revision of that acronym, which in

another context might be construed as a

form of “dignitary harm.”

Every violent crime instills terror in a

“community” – the family, loved ones, and associates of the victim. A crime of

passion, even one inspired by an irrational prejudice, is in some ways less

terrifying than one issuing from clinical indifference to the victim.

Like others who pretend that government has

a legitimate role in policing individual attitudes, Brady insists that hate

crimes laws are necessary because “some people’s minds are still so laced with

hate that we [meaning sexual minorities] may not be safe in our own

communities.”

No evidence has been produced that the

cretins accused of murdering Steven Nelson were animated by anti-gay hatred. If

this were prosecuted as a federal hate crime, as “Better Idaho” and similar groups have

demanded, any violent crime against any individual identified as a member of a

“specially protected class” would qualify for the same treatment.

Liberal Supreme Court Justice Felix

Frankfurter correctly observed that "Law is concerned with external

behavior and not with the inner life of man." The explicit purpose of hate

crimes prosecution is to use state coercion, and the threat thereof, to reform

the inner life – not of the offender, but of individuals who compose the non-offending

public.

“We recognize we cannot outlaw hate,” concedes

Wade Henderson, president of the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human

Rights. He immediately proceeded to endorse the idea that law can be used

to re-engineer attitudes: “However, laws shape attitudes. And attitudes

influence behavior.”

In their book You

Can Tell Just By Looking, and 20 Other Myths About LGBT Life and People,

authors Michael Bronski, Ann Pellegrini, and Michael Amico present

a sensible, if to some people counter-intuitive, condemnation of the hate

crimes enforcement regime. Their practical objections begin with the fact

that there is no empirical evidence that such laws actual deter crimes against people

assigned to “specially protected classes.” Some progressive groups oppose hate

crime laws, they point out, because they “are disproportionately used against

poor people and people of color,” which illustrates how the “social justice”

movement serves the interests of the prison-industrial complex.

The most compelling reason to oppose hate

crime laws, however, is the one articulated by Frankfurter decades ago: “[O]ur

legal system does not write laws to shape attitudes; it writes them to justly

and fairly punish explicit behaviors.” Actually, the

system afflicting us does nothing to protect the innocent from criminal

violence, or punish crimes against individuals – given that the evil

abstraction called the State is listed as the supposed victim in every criminal

complaint. What we might call the Frankfurter Objection to hate crime laws

underscores the way such laws destroy any remaining connection between the

state’s system of prosecution and the worthy pursuit of restitution on behalf

of the victim of an actual crime.

Defining motives for the purpose of proving

that a defendant committed a crime against persons or property is acceptable as

a means of establishing mens rea --

criminal intent. Under the hate crimes model, possession of an alleged motive

is itself treated as an actus reus --

or criminal act.

By inquiring into the opinions of the

suspect, we are introducing a third element to the offense that is not only

extraneous to the American tradition of law and justice, but -- as Frankfurter

acknowledged -- incompatible with it. The state arrogates the power to punish

the attitude, in addition to the act. This empowers inquisitors and

commissars but does nothing to protect the innocent – or vindicate victims of

violence.

This week's Freedom Zealot Podcast examines the dangers of running afoul of the Pronoun Police:

This week's Freedom Zealot Podcast examines the dangers of running afoul of the Pronoun Police:

Dum spiro, pugno!

1 comment:

can we punish state apparatchiks whose ATTITUDE we don't like? that is a rhetorical question. we all know the answer to that.

question: if a citizen is punished for an 'attitude' some snarky, pencil neck bureaucrat does not like, yet that same citizenry cannot remove apparatchiks with a bad attitude, what system does one live under?

answer: police state.

Post a Comment