You're lounging around your suburban home in pajamas on a Friday afternoon, enjoying a break from your truck driving job, when your wife informs you that a policeman is at the door. Puzzled and a bit annoyed, you greet the officer, who informs you that he spotted an expired license plate tag on a van in your driveway, and is preparing to have the vehicle towed away.

You're lounging around your suburban home in pajamas on a Friday afternoon, enjoying a break from your truck driving job, when your wife informs you that a policeman is at the door. Puzzled and a bit annoyed, you greet the officer, who informs you that he spotted an expired license plate tag on a van in your driveway, and is preparing to have the vehicle towed away.

This news triggers a spike of alarmed outrage that dispels the pleasant afternoon torpor.

“This is private property!” you exclaim. “The van isn't working, and we're planning to repair it. It's not been operated on the streets, and you have no right to tow it from here!”

The officer, believing himself clothed in the majesty of what he mistakenly calls the law, insists that under a local municipal “quality of life” ordinance he has the authority to impound your vehicle.

As you angrily but politely defend the sanctity of your property, this agent of the State does what people of his ilk always do: He invokes the ultima ratio regum by pepper-spraying you in the eyes at point-blank range and then beating you to the ground with a club.

Force is the "Last Argument of Kings" (ultima ratio regum), a phrase engraved on French artillery by order of the tyrannical King Louis XIV.

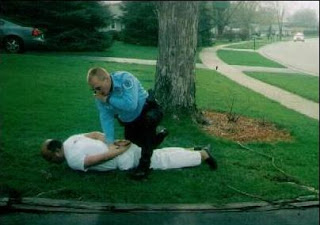

Squirming and screaming in agony, you claw at your eyes as the officer tries to slap the handcuffs on your wrists. In the background your wife and two small children are screaming in horror; after regaining her composure, your wife snaps a few photographs of the assault. Having no other options at the time, your wife then calls the police to report the ongoing assault perpetrated by one of their own.

The officer eventually succeeds in positioning you face-down on the ground, with his knee in your back, compounding the pain and temporary blindness inflicted by the pepper spray as the unyielding steel of handcuffs bites into your wrists. And during the assault, this embodiment of Official Authority leaves the air clotted with the flatulent rhetoric of racial bigotry:

“You f****** Arab! You f***** immigrant, go back to your f****** country before I kill you!”

After being dragged to the police station you are taken immediately to the emergency room, after which you spend five days in the hospital recovering from the beating you received from a supposed Peace Officer.

And as it happens, you are the one charged with “aggravated battery” because you came into physical contact with the police officer during the arrest: Your reflexive reaction to the pepper spray attack caused you to flail about wildly, making it difficult for the assailant to handcuff you. And since the officer represents the Divine State, his person is too holy to be touched by a mundane such as yourself, save under penalty of "law."

Such was the experience of Kuldip Singh Nap, 49, last March 11, as he – along with his wife and children – describe it. Mr. Nap is an immigrant. He is not, however, an Arab, “f*****g” or otherwise, but rather a Sikh. He is also a combat veteran of the first Gulf War. As his wife points out, their family has nowhere else to go, since the United States is – to borrow once again from the preferred idiom of one of Joliet's Finest – their “f*****g” country.

The official police account holds that the officer was calmly trying to explain the "procedure for removing the van" when Nap became upset and pushed him. There are four eyewitnesses who dispute that version.

A few weeks ago, I pointed out that the trend toward “quality of life” (QOL) policing “has sometimes led to replacing the anarchic violence of street criminals (or merely the unsightly spectacle of street beggars) with state-sanctioned violence.... In practice, QOL policing means the ever-increasing presence of armed government agents in the employ of revenue-starved governments, there to enforce often obscure ordinances regulating how you cut your grass, care for your lawn, paint your house, maintain your car, and even feed your dog. And intrusions of this sort can now be justified as a way of helping to keep property values up in your neighborhood -- as if anything you can do would have a bigger impact than the Fed's manipulation of the money supply.” (Emphasis added.)

At the time, I wasn't aware of the incident involving Mr. Nag, which seems like a tragically appropriate illustration of my point.

The Joliet Police Department forcefully rejects the accusation that the officer who assaulted and arrested Nag used racially abusive language. Unfortunately for him, there are, once again, four witnesses – Mrs. Vera Kaur Nag, the two children, and the victim – who can testify that he did. (There was a time – and how desperately I long for it – when policemen who used vulgar language like this, whether or not it involved racial pejoratives, would have been cashiered for a lack of character.)

Even if we set aside that issue, however, a more basic question remains, notes Chicago attorney Paul Chawla, who is representing Nag: “Does a policeman have the right to enter someone's property and tow away a parked vehicle because it has an expired tag?”

“The van was in front of Nag's garage, about fifty to sixty feet away from the street,” Chawla pointed out to me in a phone interview. “It belongs to Mr. Nag's brother-in-law, who was staying with the family, and it needs to be repaired. It hadn't been operated by anybody, and the police officer really had no reason to be there. Think of it this way: If I owned a collection of classic cars and none of them had current license plate tags, could the police come and tow them away? Of course not. They're my property – my antiques on my land. It just doesn't make sense to say otherwise.”

Under the local ordinance, according to several press accounts, inoperable automobiles can be ticketed and towed away. However, observes Rajpir Singh of the Sikh-American Legal Defense and Education Fund (SALDEF, which is providing assistance to Nag), the officer's actions were not in compliance with established policies.

“This was the first instance, the first notice of any kind Nag received that his van was in violation of the local ordinance,” Singh explained to me. “Since the van had never been ticketed before, the appropriate action would have been to leave a windshield advisory warning that it would be towed within a certain time.” Mr. Nap and his family maintain that this procedure wasn't followed.

All of this brings up another question. As Chawla pointed out to me, the license decal is a tiny rectangle that would have been difficult to spot from the street, even if the policeman had been trolling the neighborhood in search of revenue-generating code violations. Assuming that the officer didn't intrude on the Nag family's property without a warrant or probable cause of any kind, why did that van come to his attention?

“The police apparently received a telephone complaint from a neighbor,” Chawla explains. “We don't know all the details of this yet, and that's something we're hoping to learn through discovery.” Chawla, who lives in the Chicago area, claims that this particular section of Joliet, where Nag and his family have lived for more than three years, “is not all that receptive to immigrants.”

Since I don't live there, I'm entirely unqualified to say whether that assessment of local sentiment is correct. I can point out, however, that this is not the first time a US citizen of the Sikh faith has been mistaken for an “Arab” or a Muslim and been the victim of misplaced racial violence.

On September 15, 2001, Balbir Singh Sodhi (left) was gunned down at his gas station by Frank Silva Roque (right), who mistook the turbaned Sikh immigrant-entrepreneur for a Muslim. Roque went on to take shots at two others – a man of Lebanese ancestry and an Afghan family – before his shooting spree came to an end. Roque, who had pleaded insanity, was convicted of murdering Sodhi and sentenced to die by lethal injection.

As a Christian believer I have no brief for Sikh theology, and as a supporter of American independence I want no part of the ethnic and ancestral quarrels some Sikhs have with other Indian sub-communities. Having said that, I must say this as well: In the Sikhs I find quite a bit worthy of respect.

The kirpan, or ceremonial double-edged dagger that symbolizes the Sikh faith, contains a meaning that resonates with the moral vision of Christian chivalry: One cutting surface represents the innate right of self-defense, the other the moral duty to defend the weak. Sikh temples are constantly open and ready to feed anyone who is hungry. Baptized Sikhs are required to wear a kirpan, which may be either a large ceremonial sword or a small, harmless piece of jewelry.

Nanak Dev Ji (born in present-day Pakistan in 1469), founder of the Sikh faith, “was raised in a Hindu home, but repudiated Hindu polytheism,” recounted SALDEF's Rajpir Singh for my benefit. “He also rejected Islam, especially what he considered to be its denigration of women. He taught a monotheistic doctrine that emphasized a view of human equality that was very appealing to many who were living in India's caste system, in which your surname defines your status and your future. That's why Sikhs share the surname Singh – it's a statement about equality.”

Because of their distinctive customs and dress – and, more importantly, the way that multiculturalism nurtures such instances of friction into potential bonfires – some Sikhs have found it difficult to adapt to our culture. (A lot of those troubles would evaporate, incidentally, if we were to dispense with the government school cartel.) This isn't true of Mr. Nap, however, since – as noted above – he is a naturalized US citizen who served with distinction in the military before taking up residence in the Midwestern suburb.

Mr. Nag was an immigrant, but he understood the sanctity of private property and due process of law better than the home-grown Americans who are willing to act as enforcers on behalf of our burgeoning garrison state.

Obiter Dicta

Some very generous people have sent donations to keep this blog up and running; thank you so much. And I want to offer particular thanks for those who have written or called to express concern and support for Korrin. Her health has improved dramatically -- God be praised for it -- and although there's still ample reason for concern, she's doing immeasurably better than I had any reason to hope just a month and a half ago.

Please be sure to visit The Right Source.

5 comments:

I have a question: Why do we even have license tags in the first place? Or license plates, for that matter?

The best that I can figure is that we have license plates and tags on our cars so that the issuing government can re-define an individual right (freedom of movement) as a state-rationed privilege (now you can only move as the government permits), and individual property (the automobile you've bought and paid for) as a form of "collective" property -- meaning that it can be seized by an armed thug on a technicality, even when you've done no injury to other persons or their property.

As I said, the above is my best guess, because it's the only answer that makes sense, albeit of a depraved kind.

From my readings, I would suggest it was more about user fees, originally.

Briefly, vehicles became affordable and people began whining about the bad roads. Roads were more or less already considered a public utility, so state governments began taxing the primary users -- vehicles -- to fund this new liability. Early on, it was probably handled well enough, with the garnered funds actually being used to buy land, build roads, and pave them.

At some point, someone realized the civic duty of volunteer road use fees didn't produce enough to match the perceived need. Various forms of tagging to prove the tax had been paid arose, until the rather uniform policy we all recognize appeared in most states.

Things went along fine for several decades, but during my half-century of life, it became quite suddenly a rather brutal enterprise much as you describe, Will.

Well, really, the "license" was originally a voluntary "registration" that was foisted upon an unsuspecting public by assuring them that this would identify their property (vehicle) in case of theft, making location and recovery more certain. The cost of the registration was quite nominal, the funds being used only to pay for the direct costs associated with the operation of the program. The roads and so on have always been paid for by fuel taxes, the rationale being that those who use the facilities the most would pay the most money. That sounds reasonable to me.

As time passed, some bright fellow discovered that, with a bit of fiduciary sleight of hand, the costs of the registration program could be shown to increase, and the additional money could then be siphoned away to pay for other programs. When people started "doing the math" and realized that they were paying more for this "registration" than the risk of theft -- or the operation of this voluntary program -- could justify, the government(s) simply made it a requirement and called it a license. We meekly complied. Time for changes.

Another reason we have license plates is so that the vehicle can be identified. That way if a vehicle crashes into your vehicle or your child crossing the street, or if your vehicle is stolen, then the registration will help the police that you complain about can find your stolen vehicle or arrest the reckless driver.

Post a Comment